A. Islamic Council of Europe’s ‘A model of an Islamic Constitution’

B. Islamic Council of Europe’s Universal Islamic Declaration of Human Rights – 1981

C. Proposal for a ‘Muslim Electoral Registration Campaign’ – 1987

A. Islamic Council of Europe’s ‘A model of an Islamic Constitution’

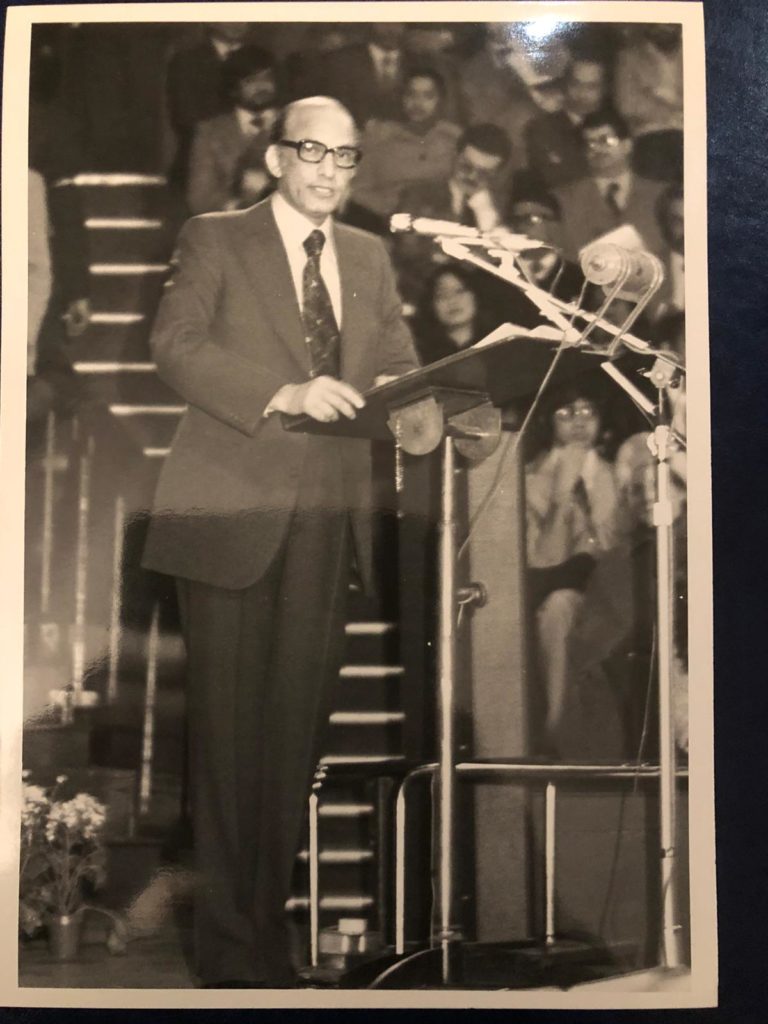

The Islamic Council of Europe (inaugurated in London in 1973) under the stewardship of the Saudi-Egyptian diplomat Salem Azzam, established a unique network of Islamic thinkers and statesmen who came together in a series of conferences and seminars held in London in the late 70s and 80s to formulate and articulate the Islamic position on a range of contemporary issues. Following a conference held at the Albert Hall in 1980 on the theme ‘Message of Muhammad’, a smaller group worked on a response to the UN Declaration of Human Rights. Those involved in its many discussions – held at the ICE’s offices in 16 Grosvenor Crescent, Hyde Park Corner – were the former Sudanese Prime Minister Sadiq Al-Mahdi, the two leading Pakistani legal experts of the day A.K. Brohi and Khalid Ishaque, and judge Midhat Azzam and Dr Kholi from Egypt. The outcomes were two seminal papers that capture Muslim thinking of the period: ‘A model of an Islamic Constitution’, published in 1983, and the ‘Universal Islamic Declaration Human Rights’ published two years ealier(see below).

That such a publication should see the light of day in a European city, rather than some part of the Muslim world, is itself telling. The pattern had been set for autocratic regimes and monarchies, sustained in power not on the basis of popular mandate but through secret police and sweet-heart deals with the USA or France. The vision of an equitable social order based on Islamic values held out the hope of a better future. The thinkers who composed this ‘model of an Islamic Constitution’ did not believe that such change was round the corner, but considered it their duty to ensure that some theoretical groundwork be put in place. The doyen of Muslim legal thinkers of the period, Abdullah Khudabaksh Brohi, himself remarked that an Islamic state could only come about in a society that was literate. The thinking was thus democratic at heart, envisaging empowerment of all people through education so that they could make informed choices.

The constitution outlines the roles of various institutions of state:

- a ‘majlis al shura’, directly elected by the people and with the authority to legislate, authorise the declaration of war, and approve international agreements

- a ‘council of ulama’, whose opinion should be sought “as necessary” by the majlis al shura, comprising of “persons well-versed in the shariah, who are known for their piety, God-consciousness and depth of knowlege and who have deep insight into contemporary issues and challenges

- a ‘supreme constitutional council’, an independent judiciary body;

- a national assembly or ‘majlis al bay’ah’ consisting of members of the majlis al shura; the council of ulama, the supreme constitutional council and higher judiciary, the election commission and the heads of the armed forces

- the hisbah – responsible for the promotion and protection of Islamic values, the investigation of complaints by individuals against the state and its organs, the protection of individual rights, the review of the work of officials of state, and monitoring and examining the legality of administrative decisions.

- an ‘imam’ – who “could be called by any other appropriate title such as Amir, President etc” – who is also elected “by an absolute majority of the country’s voters for a term of ….years, commencing from the date the bay’ah is offered to him by the majlis al bay’ah”. The model states that the “Imam shall be accountable to the people and to the majlis al shura”, while also being “entitled to obedience by all persons even if their views differ from his”. The term ‘khalifa’ is eschewed and there is no demand for the head of state to be a mujtahid

The executive powers of the imam can never become dictatorial through various safeguards, for example “the imam shall assent to legislation passed by the majlis al shura and then forward it tothe concerned authorities for implementation. He (sic) shall not have the right to veto legislation passed by the majlis; however he may refer it back to the majlis only once, within 30 days from the date of receipt, for reconsideration with his arguments. On return of the legislation after reconsideration, if passed by two-thirds majority of the members of the majlis al shura, he shall assent to the legislation”. Moreover, members of the majlis al shura would be “free to express their views during the execution of their duties, and may not be arrested, persecuted, harassed or removed from membership of the majlis al shura for so doing”.

The model constitution also affirms that “there is no compulsion in religion” and that “in matters of personal law, the minorities shall be governed by their own laws and traditions”.

In our own times, the US and Britain have assessed the balance between justice and the rule of law on the one hand, and perceived security interests on the other – and opted for the latter. The authors of the ‘model constitution’ hold that justice should be the supreme value of an Islamic state.

The debate remains whether an Islamic state is born through a bottom up movement of social change and education – as indicated by Brohi – or through a bloodless revolution, of the type articulated by Maududi -lead by a vanguard (Further reading: Hamid Enayat’s ‘Modern Islamic Political Thought’).

- Islamic Constitution – Part 1

- Islamic Constitution – Part 2

- Islamic Constitution – Part 3

- Islamic Constitution – Part 4

B. Islamic Council of Europe’s Universal Islamic Declaration of Human Rights – 1981

This 19 page pamphlet was to become one of the ICE’s most widely disseminated publications, also translated in numerous languages.

The Document articulates, in simple form, what Islam has to say on human rights and duties. It is wide-ranging and comprehensive, including clauses on human freedom, privacy, the rights of children, the right to protection against abuse of power, the right to protection against torture, and even rights after death – a deceased’s body is to be handled with due solemnity. The authors note “Islam gave to mankind an ideal code of human rights fourteen centuries ago. These rights aim at conferring honour and dignity on mankind and eliminating exploitation, oppression and injustice. Human rights are firmly rooted in the belief that God, and God alone, is the Law Giver and the Source of all human rights. Due to their Divine origin, no ruler, government, assembly or authority can curtail or violate in any way the human rights conferred by God, nor can they be surrendered”.

The Declaration is an example of competent minds’ exercising Ijtihad (independent judgement), while maintaining their allegiance to the principle of an immutable Law (the Shariah). It also demonstrates the important role played by institutions such as the ICE in offering an intellectual and physical space within which thinkers were able to discuss Islamic norms, thus providing a benchmark for the reform needed within the Muslim world.

Interestingly, the next major Muslim contribution to this effort did not surface for several decades. In 2001, AbdulKarim Soroush offered a critique of the Islamic paradigm of human rights as too ‘duties-based’, leading to a deference to power, though the ordinary man could question the application of justice. He contrasted this with the ‘rights-based’ paradigm emerging from the European Enlightenment, in which human rights stem from the nature of man. There is thus also a morality outside the umbrella of religion. Soroush contends that the absence of a declaration deeming slavery as immoral, and the tolerance of autocratic rule, are the ‘ugly faces’ of the ‘duties’ paradigm. Notwithstanding Soroush’s views, the ease with which the inheritors of the European Enlightenment have jettisoned human rights post 9/11, even legitimising torture, discredits the notion of a universal human rights based on Enlightenment norms, and reaffirms confidence in a Declaration based on Shariah.

C. Proposal for a ‘Muslim Electoral Registration Campaign’ – 1987

Click here ‘Minutes of the Steering Committee held in the Islamic Council of Europe’, 22 July 1987. Chair – Salem Azzam; Minutes prepared by S. Mukarram Ali.