Census Campaign, 2001

The religion question in the 2001 Census of for England and Wales was a landmark event for Muslims in Britain because it meant they were no longer statistically invisible with respect to social policy, local government policies and political representation . Moreover, it responded to the needs of a section of British society that was not comfortable in being solely defined in terms of ethnic categories such as ‘black’, ‘Asian’ or ‘Pakistani/Bangladeshi’. For a younger generation of British Muslims, religious identity was among the more relevant bases for self-definition.

- A. Context

- B. The work of Professor Leslie Francis’s Religious Affiliation Group

- C. The White Paper and the political engagement

- D. Further references

The ‘micro-history’ below draws on ‘A Census chronicle – reflections on the campaign for a religion question in the 2001 Census for England and Wales’, Journal of Beliefs & Values, Vol. 32, No. 1, April 2011, 1–18. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13617672.2011.549306

A. Context

The mid-1990s was a period of anxiety and reflection for Muslims in Britain. The preceding decade of Tory rule had led to considerable frustration, with reasons ranging from Home Secretary John Patten’s condescending response over the Salman Rushdie Affair, the Education Secretary Lady Blatch’s lack of sympathy with the application for voluntary aided status by Muslim faith schools and Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd’s indifference to the plight of Bosnians during the Balkan war. A survey conducted by the National Interim Committee for Muslim Unity in 1994–1995 to seek out the views and perceptions of community activists found that several respondents used precisely the same word when asked to comment on the future of Muslims in Britain: bleak. It was in this period of reflection and soul-searching that the idea for pressing for a religion question in the 2001 Census for England and Wales captured the imagination of community activists for its very audacity. It seemed an almost impossible challenge to the status quo, with its deeply entrenched view of religion as a purely personal matter with no place in public policy-making. Yet there was a reservoir of creative energy waiting to be tapped that led not only to a vigorous mobilization around the Census campaign as a cause célèbre for Muslim civil society bodies of the day, particularly the Muslim Council of Britain.

B. The work of Professor Leslie Francis’s Religious Affiliation Group

For social historians interested in dates, 11 January 1996 is significant: a minute of the Inner Cities Religious Council (ICRC) meeting held on that date records that ‘members of the faith organisations expressed general support for testing a question on religious affiliation, for possible inclusion in the 2001 Census’. The members referred to were Iqbal Sacranie and Dr Manazir Ahsan. The ICRC’s secretary was Reverend David Randolph-Horn, on secondment to the Department of the Environment from the Anglican Church, whose own passion for faith-based social activism paved the way for an initiative by ‘Churches Together in England’ to set up a working party on the religion question in the Census chaired by the Reverend Leslie Francis, Professor of Practical Theology at the University of Wales in Bangor (and also creator of the Teddy Horsley children’s stories). In its report, the Working Party made the connection between religious affiliation and matters of public policy:

Scientific research in areas of psychology, sociology, gerontology, and health care is pointing increasingly to the importance of religious indicators for predicting a range of practical outcomes … knowing about the distribution of religion within society could promote the more effective and efficient targeting of resources’ (Churches Working Together 1996).

The document provided specific examples, such as care of the elderly by religious communities, and the interplay between mental health and religious affiliation.

At the outset, the government department with Census responsibility, the Office for National Statistics (ONS), was dismissive. Nevertheless the ONS did agree to convene a consultative group, named the ‘Religious Affiliation Sub-Group’ which met on 7th August 1996. This provided a forum for faith group representatives to meet ONS civil servants and learn of Census plans, such as the testing programme for new questions. The Sub-Group members called on Professor Leslie J. Francis to take up its chairmanship. Among its prominent members was Brian Pearce, founding director of the Interfaith Network. Professor Francis’s intellectual elegance, combined with Brian Pearce’s adeptness in communicating with civil servants – based on his own years of service in the Treasury – contributed to the emergence of an effective lobby group for the faith communities. Among other prominent participants were Indarjit Singh of the Network of Sikh Organisations and Marlena Schmool of the Board of Deputies of British Jews. There was also active participation of Muslim representatives. The Sub-Group decided to draw on its networks to make representations to the ONS. Four Muslim organisations – the UK Action Committee for Islamic Affairs (UKACIA); The Islamic Foundation, Leicester, Islamia Schools Trust, London, and the Council of Mosques, Bradford, wrote directly to the Department. These efforts prompted a shift in the ONS position, noticeable in a subsequent letter received by Professor Francis in October 1996:

You will remember that at the meeting on 7 August I presented the Census Offices’ conclusions that a question on religious affiliation was not a priority need for the 2001 Census. Since then we have received further representation and have again sought the views of the main users In Government departments….we are giving thought to the form that the question might take.

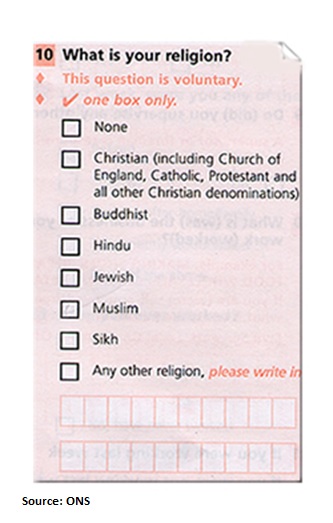

The ONS subsequently carried out its first small-scale test in March/April 1997, “to assess understanding of a prototype question on religion….twenty-seven respondents from non-white ethnic groups in Glasgow, the Midlands, Yorkshire, Southampton and London were asked to complete a test form”. A more comprehensive test was also planned for June 1997. The question took the form ‘Do you consider you belong to a religious group?’ followed by nine tick boxes: No, Christian, Buddhist, Hindu, Islam/Muslim [sic], Jewish, Sikh, Any other religion, please write below”. The ONS papers noted ominously on the small-scale test:

…in general, reactions were favourable and showed that the topic was broadly acceptable. However there was some evidence to suggest that respondents interpreted the question in different ways.

In June 1997, according to plan, the ONS conducted its second trial, this time distributing questionnaires to about 90,000 households “in a representative selection of areas across England and Scotland including Alton, Birmingham, Brent, Bridlington, Craven, Glasgow and South West Argyll”. UKACIA alerted Muslim community groups in Birmingham and Brent to ensure full cooperation with the test. The ONS’s findings corroborated the earlier test, but noted “the qualitative follow-up survey, based on in-depth interviews with those who had difficulty in completing their forms, showed that the question was understood and interpreted in a number of different ways. Some respondents thought that the question was asking about belief, others that it related to current practice….”.In the face of prevarication, Professor Leslie Francis offered this clarification to the ONS’s civil servants:

Debates within this area distinguish clearly between three distinct dimensions of religion, which are generally characterised as: belief; practice, affiliation. Questions about religious belief belong to the domain of personal matters. The census should not be concerned with matters of religious belief. Questions about religious practice (like attendance at places of worship) demonstrate the interface between the personal and the public dimension of religion. It is not proposed that the census should be concerned with religious practice. Questions about affiliation touch most closely the public and social dimensions of religion. It is proposed that the census should include a question on religious affiliation.

The members of the Sub-Group concurred that the ‘affiliation’ dimension of faith was the least problematic for Census purposes and a question could be simply put: ‘What is your religion’.

In keeping with the spirit of the times, the ONS embarked on a cost-benefit analysis for several questions in the Census, including religion and language. Census ‘users’ in central and local government were asked to submit a ‘business case’, and so too the Religious Affiliation Sub-Group. To facilitate the preparation of this document, the ONS organised meetings at which the Sub-Group could exchange views with representatives from various government departments. The discussions took place in the vast, oak-panelled rooms of Church House, Westminster, during June 1997. The impressive venue was a salutary reminder to the smaller faith groups of the Church of England’s resources and pre-eminence. The meetings themselves were conducted with utmost cordiality, even though there were often sharp differences in points of view. Some civil servants were supportive, while others, particularly the Home Office, were unconvinced of the need to complement the existing ethnic question of the 1991 Census.

The government departments’ varying degrees of support for the religion question emerged in their ‘business case’ submissions. In April 1998 the ONS informed the Sub-Group that “Census Users have produced their final version of the business cases…the [religion] question appears about two thirds down the list of priority topics according to the assessment of the business cases”.

From the perspective of the Sub-Group the ONS’s cost benefit methodology missed out on the cross-departmental and wider strategic requirements of information. For example [and hypothetically speaking] a department like Transport may justifiably inform ONS that it had no interest in a religion question. Yet it is widely accepted that in order to remove pockets of poverty and deprivation, there is also a crucial dependency between access to employment and access to transport. Transport policy cannot therefore be divorced from urban regeneration initiatives and so in the broader cross-departmental perspective there would be a need for population profiles that takes into account faith amongst other factors. Similarly, how is a cost benefit methodology to quantify the value of an increased ‘sense of belonging’ which a religion question may give to a community, otherwise statistically invisible?

Another ONS paper prepared three months later for circulation to ministers indicated that while “the proposed question is not seen as unduly burdensome ….of the three sensitive questions [ethnic group, income, religion] this has the least strong overall business case through [sic] several Departments are pressing for its inclusion; there is also support from leaders of faith organisations. But inclusion would require an amendment to primary legislation in addition to secondary legislation required for all other questions.”

By mid-1998, the prospect of a religion question appearing in the 2001 Census for England and Wales did not seem very likely. A separate internal ONS document indicates some of the behind-the-scenes discussions taking place in the department. The civil servants were alert to the arguments that had been put to them by the Sub-Group but the ‘user’ need was not yet convincing to them:

“this question would add more detail and depth to the ethnicity question, particularly the South Asian categories. It would also enable the Jews to be counted – they can be seen either as an ethnic group or as a religion

…the total number of users is less than for many other questions and the overall score for the question is therefore relatively low….the question had a good level of response in the 1997 Census Test and the quality of answers was good. In the follow-up surveys about objections to questions, religion was cited less frequently than income and ethnicity. The wording was not entirely clear to some respondents and an improved simpler wording has subsequently been tested successfully….

….there is a strong feeling in Muslim groups, and probably among the Sikhs, that their religion is more relevant to who they are than their ethnic background and there could be a significant risk to coverage and community cooperation in the areas where they are concentrated if we exclude it….

Considering all of these points, although the question did not affect the response in the Census Test, and there is some support from a variety of main users, there does not appear to be the same demonstrable strong requirement that there is for the ethnic group question. A change to legislation would be required in order to include this question in the Census and this cannot be contemplated unless there is strong support from a number of main census users, and in particular from departments where there are policy initiatives related to religion.”

The religion question had not only obtained the lowest ‘business case’ score, but it also needed additional legislative work. The ONS culture of the era made it reluctant to question the cost-benefit methodology, and to champion change and innovation. Its officials did not feel the need to respond to the public mood. Even though all the tests and trials had indicated public support, it was not willing to take the plunge itself, and instead shifted the onus of responsibility to ministers.

The head of the ONS wrote to the Economic Secretary (minister at the Treasury responsible for the ONS) asking “ministerial colleagues to indicate whether the case for the question is strong enough to warrant parliamentary time being made available to amend the Census Act”.

In a further coup-de-theatre, as if the matter was now done and dusted, the ONS informed the Sub-Group in June 1998 that it was withdrawing support: “members of the Group are welcome to continue their discussion about a religion question in the Census as an independent Group”. Chowdhury Mueenuddin, who served as a representative of Muslim bodies, has this recollection of the meeting:

“when pressed further, the ONS representative (John Dixie) conceded that ONS had not even included it in the White Paper. Members of the Sub-Group then took serious exception at this wilful omission. I then said that it would be unfortunate if the hard work of the Sub-Group went to waste in this manner. I suggested that before it was formally closed down, the official sub-group should pass a resolution and proposed the following wording, ‘It is unanimously resolved that the ONS should include the religion question in the White Paper; that the Sub-Group considers the inclusion of a question on Religious Affiliation extremely important’. The resolution was unanimously approved before the dissolution of the government-sponsored Sub-Group and formation of the unofficial group.”

The Sub-Group decided to reconstitute itself as the ‘Religious Affiliation Group’, retaining the same membership but independent of the ONS, with Professor Leslie Francis continuing to steer its deliberations with his characteristic finesse.

C. The White Paper and the political engagement

The UK General Elections of May 1997 provided the Muslim community an opportunity to raise the issue of the 2001 Census in various ways. The ‘Muslim manifesto’ prepared by the UK Action Committee on Islamic Affairs (UKACIA) – a first for Muslims in Britain with respect to its scope and range of issues addressed – included this statement that captured the rationale for the community’s campaign:

British Muslims do not perceive themselves to be an ethnic or racially-categorised community. We have always emphasised that ethnic or racially-categorisations distort a lot of perspectives and serve to make racism endemic in our society; they also make for bad laws and create major difficulties in the provision of essential services whether it is in employment, education, housing and welfare or in the dispensing of law. In this connection, we welcome the decision by the Office for National Statistics to include a question in the 2001 trial census to be carried out in selected regions of Britain. This followed an earlier outright refusal. It is still uncertain whether the question will be retained in the final version of the census form. [Elections 1997 and British Muslims – for a fair and caring society’, The UK Action Committee on Islamic Affairs, 1997]

UKACIA also organised hustings for parliamentary candidates, including the Shadow Home Secretary Jack Straw, whose own constituency of Blackburn was home to a significant Muslim population. The candidates were pressed to commit themselves to a question on religion in the 2001 Census for England and Wales, and they obliged.

By 1998 the Muslim Council of Britain had been launched and it took over the Census campaigning responsibility from UKACIA. The MCB activists were aware that discussions with the ONS were approaching a cul-de-sac. An MCB delegation meeting the Home Secretary Jack Straw in June 1998 made the case,

[the MCB] sought support for the inclusion in the national census of a question relating to religious affiliation, which is also supported by other religious groups. Mr. Straw agreed that this was an important issue but noted that the structure of the census questionnaire was still under discussion within the Government.

Faced with high-level political interest, it seems the civil servants at the ONS did not seek further controversy and the White Paper ‘The 2001 Census of Population’ published in March 1999 included a recommendation for the question, but excluded Scotland. However it stated, surprisingly in view of the tests and trials that had indicated public satisfaction with the religion question, “the Government would want to be satisfied that the inclusion of such a question in a census commanded the necessary support of the general public”.

On the one hand while the ONS was informing ministers that the question was not seen as “unduly burdensome” to the public and the challenge was of finding parliamentary time for amending the Census Act, it was also raising doubts on the level of public support. Given its commitment to one set of tools – the cost-benefit approach – it was surprising that it lacked confidence in the sampling methodologies used in three trials – the small-scale test in March 1997, the large scale test and qualitative follow-up in June1997, and the small-scale test of the revised question in December 1997 – to gauge public responses.

The White Paper also prompted some disquiet amongst several faith representatives participating in the Religious Affiliation Group, but it decided not to jeopardise what had been achieved thus far. The minutes of a meeting in April 1999 noted

…after much discussion it was decided that both ONS and the Government might regard further criticism as a reason for dropping the question altogether. The Chair was to write to ONS welcoming ‘their proposal’ of the question, noting that ideally three further faiths should be added and that the Christian category should be sub-divided….”

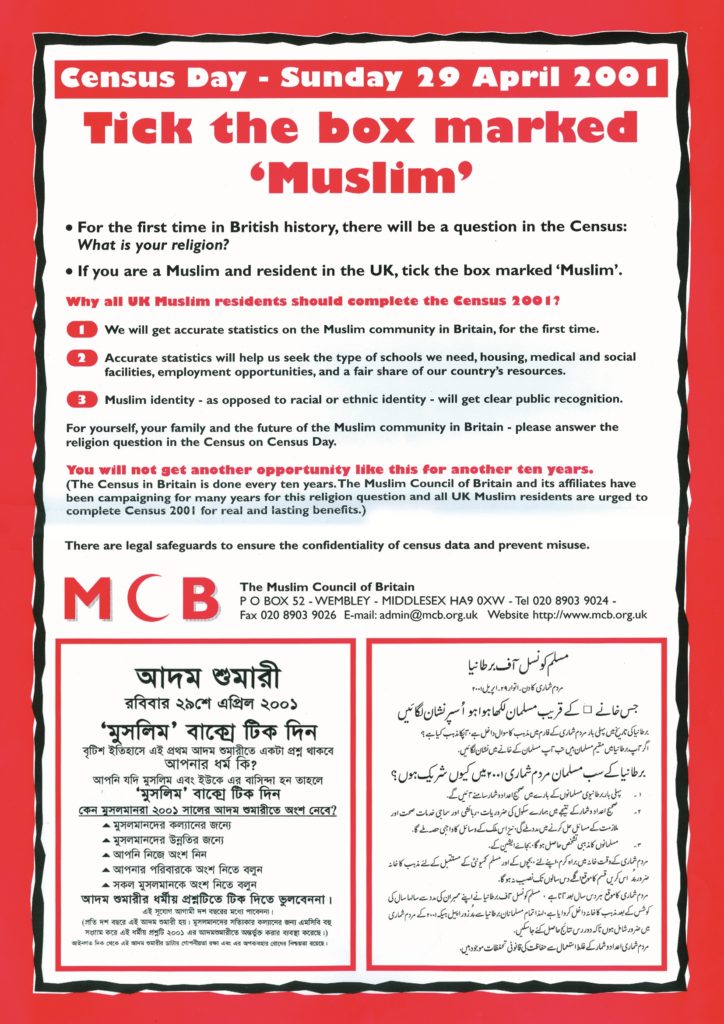

The wording in the White Paper indicated that public mobilization was needed to salvage the campaign. The MCB’s newsletter of March 1999 appealed to the community to rally round, emphasizing the strategic issues at stake:

…the MCB’s case is that the allocation of resources and the monitoring of discrimination on the basis of ethnicity alone were inadequate. Publicly-funded services and projects in areas such as health, housing, education, training and other community services can be better targeted if religion is taken into account. If it is not, large sections of the Muslim population will continue to be marginalized and disadvantaged in British society. Many Muslims do not make use of community services because these are not sensitive to their religious factor. Moreover, British Muslims, particularly British-born Muslims, identify themselves on the basis of religion rather than ethnicity or national origin. The inclusion of a religious affiliation question will also send a signal to the British Muslim community that their presence and contribution is recognized… [MCB Newsletter, Vol.1, No. 1, March 1999]

In May 1999 the MCB invited Tony Blair to a reception – the first by the Muslim community to a serving Prime Minister, at which the MCB Secretary General reminded him of some expectations for change: “[another] important matter that needs the government’s attention is on the question on religious affiliation in the 2001 Census.”

Mr. Blair in his response made a commitment: “One way of ensuring that the Muslim voice is heard is our decision to include a question on religion in the 2001 census. This will give us the information we need to take fully into account the needs of Muslim communities.”

Following the reception for the Prime Minister, the MCB wrote to Margaret Beckett then Leader of the House for her support in allocating parliamentary time for the legislative amendment needed to accommodate the religion question. The response was polite but non-committal:

“Your comments on The Muslim Council of Britain’s views on the value of including such a question in the 2001 Census have been noted. We have also passed them on to Treasury Ministers who are responsible for this area of policy. However, since we are unable to comment on the likely contents of the next Queen’s Speech, I am afraid that we are not able to add anything to what was said in the White Paper…” [25 May 1999]

However in the short-term there were more disappointments: when the Queen opened Parliament in November 1999, the Queen’s Speech made no reference to legislation needed to amend the Census Act. Without such legislation the religion question could not be put. The ONS indicated that Parliamentary approval was required no later than February 2000 in order to maintain the schedule for forms printing and agreeing processing systems with subcontractors. Time thus had to be found in both Houses within the next three months!

The first challenge was to find a peer in the House of Lords willing to propose the amendment. It is at this stage that former speaker of the Commons Lord Weatherill rose to the challenge and introduced a Private Members Bill into the House of Lords on 16th December 1999. There was an important debate in the House of Lords on 3rd February 2000 which approved the amendment, though there was a catch: Lord Weatherill in a private communication to Iqbal Sacranie, Secretary General of the MCB observed that “in order to ensure a ‘safe passage’ through the Commons it was thought wise and sensible to make the question on religion voluntary”.

The second challenge was to find parliamentary time in the Commons. For reasons unknown, the Government whips decided not to pursue the matter in government time. The frustration felt at the time is captured in this extract from a letter dated 22 May 2000 from the chair of the Religious Affiliation Group Professor Leslie Francis to the minister responsible in the Treasury, Melanie Johnson:

I now understand that following Friday’s proceedings in the House of Commons there is no prospect of the Bill being enacted through the Private Member’s procedure. If a question on religious identity is not asked in the Census, there will be no credibility in future ministerial declarations of intent to ensure the needs of different faith communities are appropriately met.”

The Secretary General of the MCB also wrote to Prime Minister Tony Blair on 24 May 2000: “I would like to bring to your attention the extremely sad reality that the Census (Amendment) Bill, which was presented as a Private Member’s bill, will certainly fail to go through on 9 June 2000 unless there is direct intervention from you or the Treasury to ensure that a few hours of Parliamentary time is given to this important Bill”.

The MCB followed up this letter to the Prime Minister with a press release on June 2000, titled ‘Identity – Faith not Ethnicity’ with this desperate message: “no further postponement is possible. The technical and administrative preparations for Census 2001 mean June 9 is make or break, if the question is to be printed on the census forms. Failure on June 9 means Muslims and members of other faith communities must wait for another 10 years to become visible as a community of faith within British society”.

Apart from reluctant civil servants, the problem now was with two filibustering opposition MPs who wished to derail all government legislation by speaking for hours so that parliamentary time allocated to debate ran out!

The MCB’s efforts continued, with Mr Sacranie also seeking the assistance of Ms Farzana Hakim, assistant political secretary to the Prime Minister and his race relations advisor. Farzana offers this recollection of the dramatic events:

…For reasons that I still do not understand, the Home Office did not include the religious question in its own Bill to put before Parliament and instead encouraged a Private Members Bill to be put in which the government would support. During this time the MCB had been in discussion with the Home Office about the coming Census Bill.

Assuming that matters were all in hand, I had by this point decided that I probably did not need to be involved any further. It was only when Iqbal Sacranie, secretary general of the MCB phoned me to say that there was a problem did I realize I still needed to be involved…

It was clear that it was very possible that the whole idea of including the religious question was about to be lost. I did two things to help.

Firstly, I informed the Prime Minister about the situation and asked what he wanted done, on the basis that we had promised we would include the question. He said it should be included. Secondly I asked his Private Secretary responsible for Parliamentary affairs what the procedure was to ensure it could be included. She asked the Business Managers in the House of Commons who said that the only way was for The Government to make a very rare exception and offer to give the private members bill government time. The last time this had happened It was clear that it was very possible that the whole idea of including the religious question was about to be lost. I did two things to help.

Firstly, I informed the Prime Minister about the situation and asked what he wanted done, on the basis that we had promised we would include the question. He said it should be included. Secondly I asked his Private Secretary responsible for Parliamentary affairs what the procedure was to ensure it could be included. She asked the Business Managers in the House of Commons who said that the only way was for the Government to make a very rare exception and offer to give the private members bill government time. The last time this had happened was for the Alton Bill some 20 or so years ago. It only happens when the Government thinks an issue is so important that it wants to make this exception. We had to go back to the PM to explain this and make sure he was happy with this. He was. The Private Secretary then had to inform the Chief Whip and Business managers about this decision and ensure it was implemented, which it was. The bill was given government time and it went through with government support.

Throughout this time, Iqbal had been phoning me at Downing Street to ensure that everything was going to plan and I was trying to assure him that it would all work – even though I was not always sure myself if we could make it happen! Thankfully everything did work out and in 2000 a question about religion was asked for the first time. But it was very nearly lost!”

The indefatigable Iqbal Sacranie also met the filibustering MPs to appeal to them to stand above party politics. His earlier acquaintance with Minister Peter Hain dating from the anti-apartheid rally days of the 70s was helpful in establishing a rapport and conveying a second message to the Leader of the House Margaret Becket to provide Parliamentary time. On 20th June 2000 Jonathan Sayeed MP present his Private Member Bill in the Commons for the amendment, which was carried 194 for, 10 against. This is the micro-history of events as they unfolded – it was touch and go to the end of the journey!

Census output on Religion data was first released in February 2003. The headline finding was that of 52 million persons counted in England and Wales, about 37 million described themselves as Christian, while the Muslim population emerged as the second largest faith community. The Muslim population of 1.6 million, including Scotland, was more than that of all the other minority faiths put together. Up to that point in time, estimates of Muslims had varied from 0.5 million to 3 million. The religion question was retained unchanged in the 2011 Census.

D. Further references

For analyses of findings of 2001 and 2011 Census data (England and Wales), key resources include:

Doctoral research by Serena Hussain conducted in 2001-2004 at the University of Bristol, supervised by Professor Tariq Modood, resulting in her publication Muslims on the Map: A National Survey of Social Trends in Britain ( London: I.B. Taurus. 2008).

Minority religions in the census: the case of British Muslims’, Religion, 2014, Vol. 44, No. 3, 414–433 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2014.927049

British Muslims in Numbers – A Demographic, Socio-economic and Health profile of Muslims in Britain drawing on the 2011 Census, published by The Muslim Council of Britain, January 2015