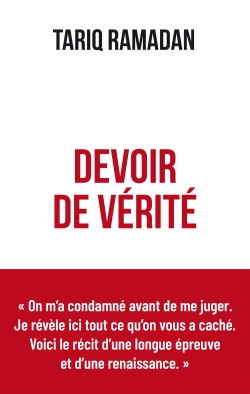

Author: Tariq Ramadan

Publisher: Presses Du Châtelet

Year: 2019

Pages: 283

ISBN: 978-2-84592-795-7

Source: https://www.pressesduchatelet.com/livre/ma-verite/

When Professor Tariq Ramadan presented himself at a Parisian police precinct on 31 January 2018, the matter seemed to him to be of little weight. Clearly investigations would reveal that the accusations against him were false and made up. Unfortunately he had not reckoned on the deeply entrenched prejudice within the ranks of the French judicial system and the nation’s literati that was ready to presume him guilty, whatever the Republic’s ostensible declarations of ‘Liberté, égalité, fraternité. There began a brutal and shameful incarceration that only ended ten months later, on 15 November 2018.

Devoir de Vérité is both a prison chronicle as well as a forensic presentation of the facts to clear his name. It is one man’s painful experiences of racism and anti-Muslim hatred, where academic credentials and intellectual sophistication can rapidly be made to count for nothing. One may be a distinguished professor and Fellow of All-Souls at the University of Oxford one day – but there were harridans at the barricades wishing for the guillotine to fall quickly and sharply. In addition to a judiciary and media ready to cut a brilliant, unapologetic Muslim to size, French Intelligence too played its role in intimidating Tariq Ramadan’s supporters. The author is not unmindful of the social context shaped by the tainted hand of the Dominique Strauss-Kahns and Harvey Weinstocks, in which allegations of sexual abuse of women were automatically assumed true.

Devoir de Vérité is also an exercise in introspection, where the author reflects on his own life and draws on spiritual resources and insights. There are poignant references to his upbringing and family. His equally brilliant father, Said Ramadan, also faced harsh times and many enemies, so there were traditions of resilience and resistance to draw on.

A pre-2018 Tariq Ramadan held store in Western values – including himself among the “Western Muslims” who were able to “unselfconsciously take an intellectual position that, in the end, acknowledges that one is speaking from home, as it were, as an accepted member of a free society . . .” In placing a revised judgement in the public domain, Devoir alsoopens up a discussion on the responsibilities of Muslim public intellectuals and their ‘sense of belonging, solidarity, with a community of suffering’ – to use Professor Tariq Modood’s phrase.

Over a century ago the ugliness of French anti-Semitism was exposed in its treatment of Alfred Dreyfus. Who is there today within the European literati with the boldness of Émile Zola to stand up in public and declare to powerful interests, ‘J’accuse’?

A Prison chronicle & the webs of collusion

In Devoir de Vérité, ProfessorRamadan describes the prison experience and exposes the bogus nature of the charges,

This book is not a plea for my defence. It brings responses to essential questions: why did the plaintiffs lie? Why was the presumption of innocence to count for nothing? Why is it, when I declared my innocence, it was concluded that I “persist in denial”? Is there a political reason for the way my dossier was handled and processed? I provide here those elements that have been omitted, ignored or suppressed . . .

On reporting to the investigating magistrate at the Police precinct on that fateful January day, Tariq Ramadan could soon sense trouble,

From their first questions I understood that no enquiry worthy of its name had been undertaken on the two women: they seemed to be the wronged victims, while I was the perfect culprit. Everything carried on as if a lid had been placed over me, “presumed guilty” the moment I crossed the threshold of this office. The attitude of the Commissioner and her assistant was less professional and more visibly hostile.

Instead of being allowed home, Tariq Ramadan was led to the police cells, and locked up for 48 hours awaiting charge. He had left home utterly unprepared, without medications and now found himself in a cellar: no mobile phones, no computers, no contact with family, including sick mother. He then found himself in front of a panel of magistrates,

I was taken from my cell from the back, handcuffed and placed in a sort of police van where there were cubicles with just enough place to sit. It was cold, at the dead of night. The lack of space made it even more suffocating. I was accompanied on board by three guards . . . there were other prisoners already there, who hurled insults at each other in loud voices . . . we arrived at the prison of Fleur-Mérogis at about one in the morning. I got down from the van and two guards escorted me to the administrator. At the entrance, by the secretariat, a wall-mounted TV was broadcasting my old images on the BFMTV channel, and at the exact moment I was in front of the administrator, the station announced that I had been placed under judicial supervision and imprisoned. Strange synchronicity.

I smiled grimly when a guard ordered me to follow him and to undress completely. My coat, like all the prison garb at Fleury, was blue. All my items were confiscated, with the exception of trousers and underwear. My shoes were confiscated because a metal lining triggered the security alarm. I was given an ‘arrivals’ kit’ of toiletries, a pull-over and some containers . . . I was cold and shivering after long hours of waiting in the mousetrap of a van. They took my photograph, a digital image of my fingerprints and provided me an inventory of items collected for signature. I was told my cell was situated in pavilion D, fourth floor, the ‘specific quarter’. I received this flood of information and categorisations without attention. I was overwhelmed by the suddenness of what had arrived my way. The prison.

The 48-hours of detention was then extended to four days, with permission to telephone his wife still denied.

A prison cell is less the room of a man than a cage for an animal . . . I stood for some minutes observing the cell. I was cold; I was exhausted. I stayed immobile. A long time. In spite of myself, tears rolled down my cheeks; I was unexpectedly overcome with sobs. I had yet to take stock of what had befallen me. I had to sit. I was on the edge of the bed in a flood of emotions. My face in my hands I thought of God, my wife, my children. Through the tears and the cup of my palms the image of my late father came before me. An extraordinary image: he is on his bed in hospital, eyes closed, already departed, face slightly inclined to the right. His fragrance – something I had not forgotten now twenty two years – invaded my senses. It was her; it was him. This was followed by the image of my mother on her bed in hospital: what will she be thinking? How was she? Can I just see her?

I was prostrate like this for an hour . . . there was mud on the window. The latch was broken. Cold air penetrated the cell creating a condensation. I tried to block the window a little but the cold air continued and I shivered . . . in my prayers that evening I implored God to grant me understanding, to give strength in the face of trials – to me, my family and those near and dear. I repeated the verse referring to how the good that we seek can be the bad that we hate. I prayed to God to allow me to grasp the trial with serenity and courage. He knows and I do not. I stayed knelt for some time and then I heard, from behind, the noise of the spy glass: the guard was observing me. He was obliged to check at all hours that I was present, alive, in good state. Not suicidal; not suicided . . . the harsh noise of the cell lock woke me at 7 . . . I got up quickly and called to the door, “Mister, if you please, Mister!’.

No one responded. I cried out and banged the cell door more strongly. After fifteen minutes a stern voice responded:

“What do you want?

– I have some questions to ask, and I am cold.

– You should wait; a staff will come and see you.

– I . . .

– Wait,” he cut me short

. . . I was tired, psychologically shaken and not quite sure what had happened. In three days my universe had been transferred . . . I suddenly remembered my medications. For the past two days I had had no access to my treatment. I was required to take several medicines for my multiple sclerosis, with one, the most important, morning and evening. I called the guard.

“ What it it? he responded with annoyance.

– I take medications and I have none with me

– It is Saturday; there is no one. Is it urgent?

I had the impression I was disturbing him. His authoritarian tone gave me a strange fear. I replied hesitantly, “Hmm . . . no, but . . . “. He cut me off quick: “So wait till Monday, when the doctors and male nurses are present . . .”

It was the abyss. I was innocent. I was in prison. In France. Is this how we treat people in this country? Is this how the innocent are treated? How is this possible? How did this come to pass?

This tragedy came to pass because of the claims of rape against him, firstly by Henda Ayari and Paule-Emma Aline, and later Mounia Rabbouj and one ‘Maimouna’. They posted on the social media to gain support and shape public discussion. The media was generous in providing them and their solicitors ample air time and column space. With the complicity of journalists with long-standing enmity to Tariq Ramadan, their version dominated and was taken as truth. The investigating magistrates gave weight to the Internet exchanges and media coverage as indicators of Tariq Ramadan’s guilt.

Meanwhile Tariq Ramadan’s health continued to deteriorate to the point where he would lie prostrate on the cell floor because of cramps. At the next hearing on 15 February the investigating magistrates refused release on the grounds that the women would be intimidated. He was transferred to a secure hospital in Corebeil-Essones on 27 February 2018, and then a month later to a specialist, secure medical facility in Fresnes. He was permitted his first phone call to family on 16 March 2018 – after 45 days incommunicado. Subsequent appearances in front of the investigating magistrates on 5 June, 18 July and 18 September followed a pattern: incredulity that Tariq Ramadan was denying the charges, and displays of understanding and sympathy for the women’s confused recollections. Tariq Ramadan engaged a more competent defence lawyer, Emmanuel Marsigny, who lodged a demand for the quashing of the detention order with the Court of Appeal. Tariq Ramadan addressed the judges directly and the appeal was upheld on 18 November, on medical grounds. Tariq Ramadan was released on surety, and his Swiss passport withheld (in case he fled to Sisi’s Egypt!). He is required to register at the police precinct weekly, awaiting his day in Court.

In one of the early hearings with the investigating magistrates, Tariq Ramadan stated that he had met Aline and Ayari only once, in 2009 and 2012 respectively. The police failed to notify the magistrates that there was a discrepancy in Aline’s statement on the time and date of encounter in October 2009: “a simple lack of administrative coordination”. Moreover, Aline’s claim of having been held against her will in a hotel room while Tariq Ramadan was delivering his talk was untrue, because CCTV footing pointed to her presence at the lecture. She had claimed to send texts from a park, but the police found was not the case. Her own doctor also confirmed her pain was more because of haemorrhoids! Moreover, four months after the alleged rape she texted Tariq Ramadan, “teach me your wisdom”. Aline claimed that Tariq Ramadan declared his intention to marry her, and she would reside “in London”. As soon as the magistrates’ hearing was over, Aline’s advocate began media briefings – and the journalists were only interested in salacious details. For Tariq Ramadan, “I had the impression of somewhat being part of a film, a piece of theatre”.

In 2014, Henda Ayari’s texts to Tariq Ramadan took on a nuisance value. He blocked her on his Facebook account but she reappeared using a pseudonym. Her messages, “alternated between sexual harassment, bondage and threats”. Tariq Ramadan notes, “all these messages were on file, but were strangely ignored or ‘forgotten’ by the magistrates and the media. Ayari came from a troubled background, which she recounted in her book, ‘I chose to be free’, published in 2016. In this, she described one ‘Zubeyr’, a “Muslim theologian”, globally renown. Soon, the media began making an association between Zubeyr and Tariq Ramadan. When the hearings began in February 2018, Ayari was asked why her book made no reference to rape. She replied it was because she did not want to be tried for defamation! Ayari also publicly acknowledged receiving financial offers from sections of the Saudi press to raise charges that would malign him.

Other women also pressed similar charges in 2018, including Bridgette ‘Maimouna’ and ‘Marie’ Mounia Rabbouj. Tariq Ramadan had met Bridgette only once at a book launch in October 2008, and Marie around 2013 or 2014. Bridgette pursued him for appearances on her Swiss TV programme, and frustrated in this regard, began contacting and harassing Tariq Ramadan’s family; there never was any reference to rape. Mounia Rabbouj was also an ardent sender of texts, who, according to her brother, was seeking some financial gain. Devoir draws attention to the contacts these women had with each other, sometimes resulting in very similar expressions to describe their so-called ordeal: for example their attacker’s grotesque change of facial expression! Ayari was in touch with Maimouna, as was her advocate, Eric Morain. However, more importantly is the behind-the-scenes role of the French journalist Catherine Fourest.

Over fifteen years ago, in 2004, Fourest wrote the polemic, Frère Tariq, Le double discours de Tariq Ramadan (Brother Tariq, The doublespeak of Tariq Ramadan), with a foreword by Denis MacShane, then a Member of Parliament. In this book and subsequent works, she carried the anti-clericism not uncommon in a class of French intellectuals to obsessive lengths. As indicated by the title, the aim was to ‘expose’ Tariq Ramadan as an hypocrite, liar and worse. She identified the ‘doublespeak’ at several levels: the aspiration for Muslims to integrate in Europe, but also adhering to Islamic values; the fundamentalist wolf in sheep’s clothing; the language of goodwill and harmony belying an agenda of European conquest. She notes how Hasan al-Banna’s programme in Egypt sent “shivers up and down one’s spine”; “wherever he goes, Ramadan spreads the form of Islamism that he inherited”; ‘taqiyya’ (dissimulation) “is used by Islamists living in the Western democracies, not in order to avoid arrest, but simply a means for pursing their ends while remaining disguised.” She claims that Tariq Ramadan concealed the fact that he was ‘trained’ at the Islamic Foundation, Leicester – “an Islamist institute whose mission was to use England as a base for spreading the doctrines of Maududi and Qutb”, where The Satanic verses was “an object of abhorrence” – but this duplicity was no longer necessary when the institution received “official recognition”. With complete lack of scruple, Devoir made a fantastic and unfounded attribution: ‘to say the murder of a Christian woman or child on the London tube is to be deplored, but the murder of a Jewish child or mother on a Tel Aviv bus is not to be condemned with equal vigour is to enter a moral universe that all decent people should shun”.

Catherine Fourest had known Paule-Emma Aline since 2009 and interviewed her for the magazine Marianne in November 2017 to coincide with the charges lodged with the police. The piece repeated allegations of Tariq Ramadan’s ‘double speak’ and ‘double life’. Fourest’s feverish imagination considered that Tariq Ramadan had a “hypocritical and misogynistic pathology . . . a preacher obsessed with sexuality, betraying a more personal neurosis. When I think of all the fundamentalist Christian or Islamist preachers I have investigated, I do not think I have ever come across a man who had a balanced sex life or simply conformed to what he preached. The world is full of homophobic televangelists with homosexual relations, paedophile priests and Islamist sex predators.”

There were others too with Tariq Ramadan in their cross-hairs and awaiting their opportunity to be his nemesis. Michael Gove, in Celsius 7/7, How the West’s policy of appeasement has provoked yet more fundamentalist terror – and what has to be done now (2006) decried the appointment by the University of Oxford of someone who “gives it a pretty good try” to follow in the footsteps of his grandfather. Gove quoted Tariq Ramadan’s statement, “In Palestine, Iraq, Chechnya, there is a situation of oppression, repression and dictatorship.” Melanie Phillips’s equally polemical Londonistan,How Britain is creating a terror state within (2006) declared that Tariq Ramadan “has a record of extremist statements and telling evasions . . . his message is that Islam is the solution to the problems of the West . . . In his book, The Islam in Question, he wrote that he strongly favoured the death of the ‘Zionist entity’. . .he has extolled Shaikh Qaradawi, openly supported Hamas as a ‘resistance’ movement. . .” Tariq Ramadan’s outspoken support for the for the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement at the Palestine solidarity event in London organised by Friends of Al-Aqsa in 2017 would also not have gone unnoticed.

Tariq Ramadan provides evidence of the complot involving Catherine Fourest,

“between 6 May and 6 November 2017, six months before the depositions of the two complaints, and three months after, investigations reveal that there were fifty-six contacts (telephone calls or SMS) between Caroline Fourest and Mme Henda Ayari and one hundred and sixteen between Caroline Fourest and Mme Paule-Emma Aline. My advocate has never ceased seeking access to the ‘handles’, details and dates of exchanges, but strangely, the magistrates had not sought to obtain them, or seek for it themselves for significant information . . . Investigations in August 2019 reveal that she [Caroline Fourest] remained active in constant communication with the plaintiffs: she had 245 contacts with Mme Paule-Emma Aline from October 2017 to July 2018, and one hundred and twenty with Mme Henda Ayari between October 2017 and the start of February 2018 (always from her company’s phone). One should seek to demand the nature of her involvement in this affair.”

Fourest has also had proven contacts with Bridgette ‘Maimouna’.

The drama brings to mind To Kill a Mockingbird, the famous novel set in the US deep South in which a young black man is falsely accused of rape of a young white woman and a lynch mob is on the ready. The French literati elite comprising Fourest, Bernard-Henri Lévy, Bernadette Sauvage, Giles Kepel, Lucia Canovi et. al set aside the presumption of innocence and prepared to see a man sent to prison for 20 years. A modern media lynching no less.

Tariq Ramadan admits to his vulnerabilities. To err is human. A frank passage in Devoir is one of contrition,

I am not a rapist. The notion of abusing a woman against her will and to revel in her suffering is utterly foreign to me and horrifies me. It is not me. I can only live if there is consensuality. Whatever be the nature of a relationship – and even if words when take out of a context of play and being in league can surprise – I have never spoken, written or acted but with the accord of the woman, her consent, her complicity and, more often, her demand. This is what all the messages retrieved so far prove. I have never exerted a ‘religious grip’, or ‘psychology’; I have never manipulated or forced conduct or practices, and even less ‘rape’. I have sometimes lacked clarity in, and minimised, – this is a fault – the emotional attachment and expectation that can be prompted by accepting to a virtual game or meeting. In this sense, I was negligent with certain women and I did not behave in a dignified way. I do not speak here specifically about intimate relationships or sexuality . . .

I was living at a fast pace, between air flights, without the time I needed to attend to myself or clarify matters. Thus, it came to pass for me to forget, to be careless, and to see how, quite understandably, hearts, intimacies and egos were hurt. My inattentiveness, even clumsiness, was perceived as arrogance and contempt . . . I even heard this in the bosom of my family. The time in prison allowed my conscience to become well-cognisant of these criticisms. I now know this from the inside of my being. Me, who would cite Rimbaud – “those who meet me, perhaps did not see me” – and who called others to be better in seeing – had often seen, not considered. I was short of attentiveness. “Live a hundred percent in the hour”, occupied in a thousand projects, each as important as the other . . .

Elsewhere, he reflects on an on-the-move self-absorbed life style which led him to overlook his near and dear,

The cell door opened. The guards let in my wife followed by my daughter. We looked at each other intensely, in a silence that conveyed all in one love, sadness, suffering and fear. I was not at ease. My wife, Iman, had lost weight and my daughter Maryam was also affected. It took us some minutes to find our bearings, to be able to converse, wipe away the tears and smile. I will never forget that instance . . . after I left prison I confided in them that it seemed to me that I had found not just my wife and my daughter, but two members of the resistance, two fighters. My wife looked at me with a smile and this riposte: “we were always so but you did not acknowledge”. She had reason. I had not seen. I had not known how to see.

Devoir provides many examples of the inhuman and degrading aspects of the French criminal justice system, but also the presence of sympathetic individuals amongst the guards and prison medical staff, whose one kind word would make a difference. Tariq Ramadan was denied Arabic books, including Sufi texts (he had requested Qushairi’s Al-Risala): “in prison it seems that the Arabic language itself. A terrorist language . . .” A medical report indicating that imprisonment was damaging his health was dismissed with contempt – “what is this note of this Dr Fariiid”, as if an Arab doctor would not be competent. There are shocking references to the efforts of the police to intimidate Iman, Maryam and others, certain police staff sought to drag my name through the mud during interrogations and to convey falsehoods to obtain information by all means possible. These policemen did not hesitate to apply pressure, rudeness and menace when the responses did not match their expectations . . . officials of the DGSI, mayors and even the state officials intervened to warn supporters of my cause of grave consequences for them and their families.

In spite of this intimidation, there many individuals and groups who rallied in his support, including demonstrators who held vigils outside the prison. Devoir mentions an Oxford colleague, but leaves his name as ‘Cosmo’. Others who stood by him in France included Houria Bouteldja, Francois Burgat, Alain Gabon, Michele Sibony and Fanny Bauer-Menti. The Muslim Council of Britain, to its credit, did not remain silent and took up his case in a letter to the French ambassador in September 2018. It pointed to double standards if the presumption of innocence until proven guilty could apply to say Nicolas Sarkozy, when accused of electoral fraud in 2012, or Christine Lagarde over allegedly pay-offs to tycoon Bernard Tapie in 2008 when she was France’s finance minister; neither was placed under pre-trial detention – Tariq Ramadan received a treatment normally reserved for terrorism suspects.

Tariq Ramadan’s important contribution has been to offer European Muslims a coherent conceptual schema in which an authentic Islamic identity is co-terminus with national citizenship and civic engagement. In 1999, his To Be a European Muslim identified the “fundamental need”: from the Muslims’ point of view . . . they should acquire the confidence that they are at home and they must become more involved within European societies, which are henceforth their own, at all levels, from strictly religious affairs to social concerns in the broad sense. In Western Muslims and the Future of Islam (2004) there was a call for them ‘”to settle on the spiritual and ethnical modalities of a harmonious life through a real integration of the deep things of life. . . it requires that we be here, that we really exist here, and that out of the very heart of Western culture, we find the means to sustain ourselves, to outdo ourselves, and to become capable of making our own contribution . . . We shall have to liberate ourselves . . . by developing a rich, positive and participatory presence in the West that must contribute from within to debates about the universality of values, globalisation, ethics and the meaning of life in modern times.” In Devoir, there is chastened voice that speaks out – with allusions to St Augustine’s model of governance – the City of God –Nietzche and Zola. It is characteristically reasonable and fair-minded, but now with a glint of steel,

I am an ‘Occidental’ and a ‘European Muslim’, and paradoxically I have never been so much a European as in this affair . . . the ‘Ramadan Affair’ is European and occidental. It goes beyond my situation. It is included in history: it speaks of the tensions and strains of today, and also heralds other ones of tomorrow. At a personal, human level, I am a European searching a way between his principles and the development of faculties in the City . . . if a person is a role model, it is not specifically because of the beauty of his expression, but in his fragilities, his moral struggle and efforts to become better . . .even though this affair is not over, I know that I emerge stronger, if it pleases God and the thousands of women and men who are with me. In Twilight of Idols Nietzsche declared that ‘who does not kill me, makes me stronger ‘ . . . One must be patient . Zola said, “Truth unfolds and nothing stops it”. I continue to have confidence in justice, in spite of a profound distrust of the judges. I have seen their biases and their ways. I also know the destructive force of journalists and the media. I have no illusions of the hypocrisy and their capacity to spread lies, terror and death in advancing their interests and career. I will continue to resist. I will not let anything go.”

Welcome to the Resistance. Devoir is beautifully written, with an oft-repeated and haunting phrase: peace is the daughter of suffering – la paix est fille de la souffrance . Our prayers are with Tariq Ramadan, Ameen.

Jamil Sherif, November 2019.© salaam.co.uk