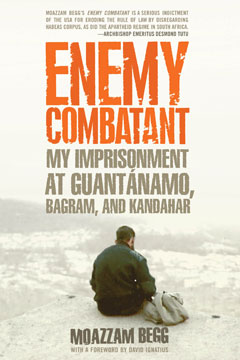

Author: Moazzam Begg with Victoria Brittain, Enemy Combatant

Published: London Free Press,

Year: 2006. Pp. 395.

ISBN: 0-7432-8567-0 (HB).

Source: https://thenewpress.com/books/enemy-combatant

This is the first full account by one of the nine British citizens formerly held at Guantánamo, the American military base in Cuba. Moazzam Begg’s faith, integrity, humanity, idealism and courageous resilience come through in every page of this harrowing story. It is all the more moving for the precise matter-of-fact language used to record even the grisliest moments. [1]

Most of this book is, as the subtitle suggests, Moazzam’s journey to Guantánamo and back. It starts with his extra-judicial kidnapping in Islamabad in January 2002 by the Pakistanis at the behest of the Americans to whom he is quickly handed over. Incarcerated for three years, Begg is interrogated over 300 times, forced to sign a fictitious confession, witnesses the death of two inmates during his time at Bagram Airbase in Afghanistan, and is subjected to solitary confinement for two years in a “steel cage” (p. 194). Begg’s account gives us an inside look at a new global Gulag, a string of military bases designed to be beyond the reach of judicial scrutiny. In this account, Bagram conducts an even harsher regime than Guantánamo, although the use of torture has taken place at “Gitmo” too, according to declassified FBI documents.

Yet parts of the global Gulag remain completely inaccessible: off-the-radar “black sites” or the “extraordinary renditions” to partner Muslim countries in the “war on terror” like Egypt that have little or no regard for basic human rights. At one terrifying moment, Moazzam faces the prospect of such a rendition to Egypt straight from Bagram, but is reprieved at the last moment (pp. 157-159). It should be noted that, from 1998 onwards, Moazzam was “shadowed” by designated MI5 operatives who later question him during his period of internment, demonstrating the complicity of British intelligence and other officials in the US’s global Gulag, even with respect to their own British citizens (e.g. see the pointed exchange between Moazzam and “Andrew”, his MI5 handler, at Bagram on this very issue, pp. 166-167). Only in May 2006 has a senior British minister, Lord Goldsmith, the Attorney-General, called for the closure of Guantánamo. [2]

Begg’s status as “enemy combatant” is a designation beyond either the Geneva Conventions enforcing the fair treatment of prisoners of war or normal criminal law, although this non-juridical status, and the need for proper legal process, is being increasingly challenged by human rights lawyers. For their key role in Moazzam’s eventual release in January 2005, British lawyers Gareth Pierce and Clive Stafford-Smith come across as real heroes. Although all nine British citizens have now been released, nine British residents remain in Guantánamo at the time of writing.

In this personal and honest account, Begg lays three myths to rest. The first is the stereotype of the angry, manipulable and confused Muslim youth, whose concern for the state of crisis in the Muslim world triggers a predictable pathway. Born and bred in Birmingham, Begg recalls his family’s martial tradition, which stretches from the Mughal emperors to the British Indian army, later abandoned for the professions, as his grandfather felt that modern war targeted the innocent and lacked the once-intrinsic virtues of honour and courage. What comes across from Begg’s pre-Guantánamo years is a strong idealistic support for the underdog and an impassioned desire to help them directly. In his teens, he was a member of a multiethnic gang, the Lynx, which defended black communities from the incursions of white racist thugs. There are similar racial tensions in the early life of French citizen Zacarias Moussaoui, the only person to be convicted of terrorist offences in connection with 9/11. [3]

In the early 1990s, Begg was drawn into the great causes of Muslim suffering, in particular with the plight of the Bosnians – unable to defend themselves due to an arms embargo – which presages a political awakening leading then to a greater interest in his faith. Subsequent visits for aid distribution or personal curiosity took him to Bosnia, Pakistan and Afghanistan, including some short excursions to mujahidin training camps, although Begg never saw any combat action. In 1997, he set up an Islamic bookstore in Birmingham, partly to promote Muslim causes of self-determination. In 2001, he left with his family to set up an Arabic language school in Kabul, viewing, with some reservations, the Taliban’s Afghanistan as a good Islamic society, but left for Pakistan soon after 9/11, seeking a safety that was to prove short-lived.

The second myth exploded here is the tendency to conflate separate strands of jihadi Salafism, let alone disparate national causes, civil conflicts and insurgencies together under the catch-all “al-Qaeda”, a term first employed to describe Bin Laden’s database of jihadi volunteers, started in 1988. [4] It was only used by the Americans to describe something like an organisation in 1998; Bin Laden only publicly used the term himself after 9/11. Moazzam appears to have been inspired more by the strand represented by Abdullah Azzam (1941-1989), the chief theorist of the Afghan jihad against the Soviets (p. 81). In the wake of Soviet withdrawal, Azzam argued for the formation of a jihadi vanguard that would defend the Muslim lands from attack, insisting that to do so was the individual duty of every Muslim. (Most jurists stipulate that the recognised political authority able to call for a jihad is the state and not the individual, although this condition lapses in cases of immediate self-defence.) However, unlike Bin Laden, Azzam insisted that only military targets in times of war were legitimate.

Whilst in Guantánamo, Moazzam, in a long religious dispute with a self-declared al-Qaeda member, Uthman al-Harbi, argues clearly against the targeting of innocents (pp. 304-309). Echoing his grandfather’s sentiments, Begg sticks to a perhaps now romantic notion of honourable jihadism in this era of total war and the post-9/11 US “doctrine of pre-emption” and “full spectrum dominance”. Al-Harbi replies that modern weaponry is indiscriminate, and that the wide collateral damage in the Muslim world deserves a similar response. Thus it seems that in Islam, as with other religious traditions, traditional codes of ethical conduct in wartime are under immense pressure to accept the “realpolitik” of civilian casualties. [5] Moazzam is viewed by his American captors as just another al-Qaeda member like Uthman, despite the crucial differences between them. The danger of escalation with such conflation is obvious: it merges causes of self-determination in the Muslim world with terrorist attacks upon civilians within the Muslim world and in the West.

In fact far from being the “worst of the worst” as President Bush described them, 90% of those held at Guantánamo had no intelligence value whatsoever and most were not fighting when they were captured according to a former second-in-command at the base, Brigadier-General Martin Lucenti. In one moment of black farce, Moazzam’s Kabuli greengrocer joins in him in Bagram turned in for money as an (obviously spurious) “al-Qaeda sympathiser” (p. 164).

The final myth to be broken is Moazzam’s painful discovery that very ordinary people perform cruel acts; in other words that the global Gulag, like other similar examples from the past, bears out Hannah Arendt’s dictum about the “banality of evil”. [6] Moazzam’s ability to reach out to his captors in a humanizing way again and again over the course of three years is quite extraordinary. Many of his guards appear to be very ordinary, with simple ambitions and common preoccupations, are often radically ignorant about Muslim history, faith and culture, and myopic with respect to the human rights abuses around them. In many cases, most surprisingly with a racist “redneck” former Vietnam vet, Moazzam is able to get through this hostility, in this instance through recounting that former war, so that the man laments that Moazzam and others are not afforded the dignities of the Geneva Convention (p. 235). But towards the end of his incarceration, Moazzam’s ability to form individual connections no longer masks the relentlessness of Guantánamo’s regime, a feeling that intensifies as the fragile prospect of freedom approaches.

This is a book that has to be read for an inspiring story of human resilience, for understanding the powerful idealism behind much of today’s jihadism (that sets its face against targeting civilians), and for the brutal realities of the global Gulag, a vital component in the “war on terror”.

[1] An important complement to this memoirs is British director Michael Winterbottom’s film, The Road to Guantánamo (2005), which tells a tale of innocence betrayed, of the Tipton Three – Ruhal Ahmed, Asif Iqbal, and Shafiq Rasul – three young British lads naively caught out in the American invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

[2] Washington Post, 11 May 2006.

[3] See the account by his brother, Abd Samad Moussaoui with Florence Bouquillat, Zacarias Moussaoui: The Making of a Terrorist, translated by S. Pleasance and F. Woods (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2003).

[4] Gilles Kepel, Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam, translated by A. F. Roberts (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2002), p. 315.

[5] For an overview of a similar discussion among British Christians during the Second World War, see Abdal Hakim Murad, “Bombing without Moonlight: The Origins of Suicidal Terrorism” (2004), available at www.masud.co.uk, accessed 12 May 2006.

[6] Eichmann in Jerusalem: a Report on the Banality of Evil (London: Faber & Faber, 1963).