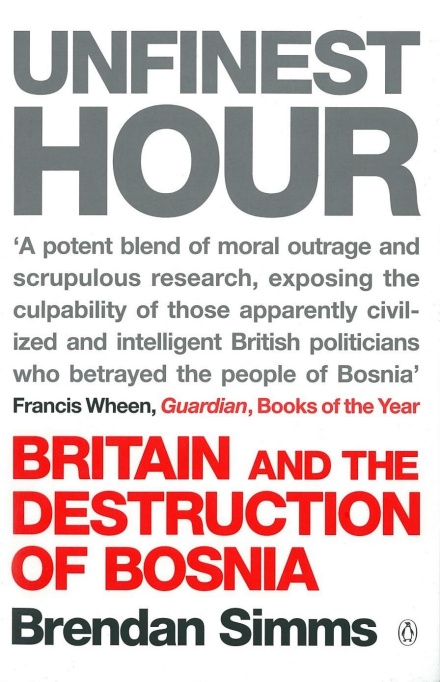

Author: Brendan Simms

Published: Allen Lane,

Year: 2001

Source: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/25849/unfinest-hour/9780141937670.html

Bosnia-Hercegovina emerged as an independent nation in April 1992, with the leader of the Democratic Action Party, Alija Izetbegovic, elected President, heading a three-member Presidency. A number of other nations also emerged from the ashes of old Yugoslavia: Croatia, Slovenia and Serbia. Bosnia-Hercegovina was legally recognised as a sovereign state with full representation at the United Nations.

From the outset, Croatia and Serbia did not disguise their ambitions to acquire territory in Bosnia-Hercegovina. The British Foreign Office consistently refused to accept this as external aggression against a sovereign nation, and termed it as ‘civil war’. While Croatia and Serbia had the patronage of Germany and Russia respectively, Bosnia was effectively an orphan nation that was easy prey to high-handedness and coercion. Britain refused to set up an embassy in Sarajevo for almost two years.

Brendan Simms’ outstanding book portrays how John Major’s Conservative Government manufactured a policy on Bosnia in the period 1991-95 that was unsustainable on moral grounds. A coterie of British statesmen succeeded in imposing this policy through a combination of bravura and manipulation. Brendan Simms laments, “neither the press nor the intelligentsia proved capable of mounting a serious challenge to the prevailing consensus”.

The Balkan crisis of the early 1990s provided Foreign Secretary Hurd and other grandees – Ex-Foreign Secretary and NATO Secretary General Lord

Carrington, Defence Secretary Douglas Rifkind, Foreign Office minister Douglas Hogg, ex-Foreign Secretary and the European Union’s Balkan negotiator Lord Owen – an opportunity to indulge in power play on the world stage. Issues of national sovereignty and genocide took second place in the desire to impose a British solution to the problem – the emergence of a ‘Greater Serbia’ and the partitioning of Bosnia-Hercegovina. Their minds were closed to the tremendous potential of Bosnia-Hercegovina serving as a model example of a multiethnic, multicultural state in Europe. Any one seeking to preserve the territorial integrity of Bosnia-Hercegovina was ridiculed and belittled. Carrington dismissed Izetbegovic, a distinguished intellectual and author, as that ‘dreadful little man’, much like Mountbatten had belittled Mohamed Ali Jinnah on the Pakistan issue fifty years previously.

Brendan Simms traces each move taken by this British pro-Serbian coterie:

“Britain was alone in opposing the idea of armed intervention to safeguard the passage of humanitarian aid in the Bosnian conflict. Then, throughout late 1992, and early 1993, Britain resisted the imposition of a ‘no-fly zone’ principally directed against the Bosnian Serbs and their Yugoslav backers for as long as it could; thereafter, Britain obstructed the actual implementation of that ban as long as possible. At the same time, Britain dismissed US plans for aid flights to isolated Bosnian government enclaves as mere gimmicks likely to provoke the Serbs to yet more terrible retaliation which might engender the whole aid effort. Britain abstained on a UN General Assembly resolution in December 1992 comparing ethnic cleansing to genocide, and opposed a similar motion at a session of the UN Human Rights Commission”.

The British policy makers were at all times fully conversant with the facts on the ground. In September 1991, the US Secretary of State, James Baker, had warned the UN Security Council of aggressive preparations by Bosnian Serbs. Both Whitehall and the US State Department were aware of atrocities in Serbian camps in the summer of 1992. In the autumn of 1992, George Kenney, the Deputy Head of Yugoslav Affairs in the State Department resigned because of the inability of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe to deal with genocide. In 1993, even Douglas Hogg acknowledged in Parliament that there were ‘clearly close parallels in moral terms between what has happened in Bosnia and what happened in Germany as a result of Nazi policy’.

Simms notes that “so frustrated were the Bosnians with British policy and with her vigorous maintenance of the arms embargo against the legitimate government in Sarajevo, that they threatened to charge Britain before the International Court of Justice as an accomplice to genocide. A letter to that effect was sent to the Security Council in late November 1993”.

On leaving the House of Commons after the 1997 elections, Hurd became the deputy chairman of NatWest Markets and worked out a deal to privatise Serbia’s telecoms service. In this light, Simms’ comment, “Britain’s response to the crisis reflected a failure not so much of morality, as of judgement”, is over generous. Milosovic is now threatening to reveal secret deals at his trial in The Hague. A senior Foreign Office official recently made a clumsy attempt to deflect this threat by stating, “We will not be surprised if Lord Hurd’s dealings with Milosovic are raised during the trial but, in fact, our hands are clean. We have nothing to hide. The French government may well be nervous about its own friendly relationship with Milosovic right up to 1999”.

Hurd and his coterie devised a number of formulations and strategies to conceal their policy interests and confuse the public. First, to blur the distinction between aggressor and victim and establish an equivalence between the legitimate Bosnian Government on the one hand and the Croat and Bosnian separatists who were aided by Zaghreb and Belgrade respectively on the other. Second, to threaten that external armed intervention to prevent ethnic cleansing would ‘jeopardise the humanitarian effort’. Third was the exaggerated sense of Serb military prowess.

The argument of equivalence

Brendan Simms points out the use of language of ‘parties’ and ‘factions’ to convey an image of equivalence. For example Douglas Hurd observed in early 1974: ‘as we can see very clearly in Bosnia, the only people who can stop the fighting are the people doing the fighting. You have at the moment, alas, three parties in Bosnia, who each of them believe that some military success awaits them’. A particularly callous example was the obfuscation when mortars landed in a Sarajevo shopping centre:

“Sometimes government ministers even took their lead from UNPROFOR – including British officers – and implied that the Bosnians were shelling their own people, particularly after the marketplace massacre in February 1994. Thus the Minister for Overseas Development, Baroness Chalker, found it ‘impossible’ to tell an MP ‘who is responsible for the shelling in Sarajevo. All I can tell him is that the investigations by UNPROFOR [the UN Protection Force] have been going on. While it cannot be said with certainty who was responsible for the 70 or so deaths that were caused, we certainly know that there were many people who could have doing it on both sides of Sarajevo’. Subsequently, the Prime Minister stated that, although he thought the Serbs the most obvious culprits, a later report had implicated Bosnian government forces. In his view, either side was fully capable of perpetrating such an act’. John Major, of course, did not need certainty, he merely needed sufficient doubt to blur the issue and dilute the call for an international response. Alistair Goodlad, the Minister of State at the FCO, advanced the same argument in more general terms. He observed after the market-place massacre of February 1994 that ‘We are looking for effective action – if necessary, muscular action – to protect the civilian population of Sarajevo. They have been subjected to mortar attacks from both Serian and Bosnian forces’. Of course, the notion that the seige of Sarajevo – surrounded on all sides by Serb heavy weapons and defended by undergunned Bosnians – was somehow a joint effort between the ‘parties’, was quite absurd.

When challenged by one MP to ‘recognise that the conflict is clearly part of the campaign for the creation of a Greater Serbia’, the Defence Secretary in turn called upon him to ‘accept that the Croatians have been seeking to control as much territory as possible in Bosnia…and I have no doubt that the Bosnian Muslims [sic], given the opportunity, would also be seeking to do so.’ In short, the Bosnian government might not have committed comparable atrocities to Serb separatists, but they would surely do so if they had half a chance, particularly if the international arms embargo were to be lifted. Again generous to a fault, Brendan Simms concludes that ‘this insistence on moral equivalence stemmed in part from ignorance and intellectual laziness”.

When Lord Owen was appointed by Prime Minister John Major as the EU mediator, he was initially supportive of stronger action against the Serbs. However he changed his line and adopted the official vocabulary: “I have come to realise, and say publicly, that there were no innocents among the political and military leaders in all three parties in Bosnia-Herzegovina.” In June 1993, Owen added, ‘all three constituent nations in Bosnia and Herzegovina fight and cleanse each other’. Simms believes that the reason for Owen’s change was the insidious ‘education he received from Whitehall. The outgoing EU mediator Carrington recalls this briefing he gave Owen:”We had a very long chat. He [Owen] went in with the idea that the Serbs were the demons…And being an intelligent man, he wasn’t there for ten minutes before he realised that it was a great deal more complicated than he realised, and that they were all as bad as each other”. Owen also remarked that the Foreign Office would have ‘taken his legs off’ if he did not advocate British policies.

The moral equivalence became translated to military terms as well. Ivor Roberts, the British charge d’affaires in Belgrade in 1995 argued that ‘It is not an embargo on one of the three parties but on them all. As the war has shown, all sides have disposed of large quantities of weapons and ammunitions’. Roberts completely glosses the point that the embargo perpetuated the enormous imbalance of weapons in the Serbs’ favour at the beginning of the war.

The FCO ‘spin’ of moral equivalence penetrated the media, and more damagingly, the British officers serving in UNPROFOR. Coughlin ofthe Sunday Telegraph frequently aired the view that it was a misapprehension to view the Serbs as the primary culprits. Simms also notes that by 1995, ‘it appeared that the Independent was ingesting Whitehall spin no longer by osmosis but by direct injection.’ The military top brass making up UNPROFOR, were drawn from the same elite class as the FCO coterie. General Michael Rose, the first British commander of the force, was an Oxford graduate with an exaggerated air of superiority. In March 1994, he observed, “I wander around and talk to them [the people of Sarajevo] and say ‘Look, if you want this goddam senseless killing to stop it will stop. You must make this plain to your own politicians in as tough a way as we are doing’.” Rose’s press officer Colonel Tim Spicer would write in his memoirs that ‘in the Balkans they are all as bad as each other’. His chief of operations, Lt. Col Christopher le Hardy stated that in his view ‘all the factional leaders are rotten through and through’.

This posture of equivalence required the British to play down the gravity of serious atrocities committed by the Serb army. Most notoriously, after the fall of the ‘safe haven’ enclave of Srebrenica and the massacre of thousands of men in July 1955, Simms provides references to how the Ministry of Defence ‘went on the offensive working to deny and play down evidence of a massacre’.

Brendan Simms reminds readers of the untruth of the assertion that all sides were equally guilty:

“Between April 1992 and October 1995 a European country was destroyed. Tens of thousands of its inhabitants were murdered. More than a million were expelled, deported, or fled in fear of their lives. An unknown number were raped, humiliated, and traumatised…the primary and original transgressors were the Serb radical nationalists led by Radovan Karadzic and General Ratko Mladic, and their sponsors in Belgrade. Unlike the Bosnian government side, which never entirely lost its distinctive multi-ethnic complexion, these Serbs aimed to create an ethnically pure state, from which all trace of its former Muslim heritage had been eradicated. All the mosques in Serb-occupied areas were destroyed; the majority of Catholic and Orthodox churches in Bosnian-held territory survived more or less intact. And whereas many Serbs and Croats, particularly in urban areas, loyally supported the Bosnian government throughout out the war, virtually all Croats and Muslims were expelled from Serb-held Bosnia. There was no equivalence between the Bosnian government and its Serb nationalist assailants”.

Simms refers to a meeting on 22 January 1993 attended by Major, Hurd, Rifkind and Owen. In attendance was also Brigadier Andrew Cumming, a serving officer in Bosnia. In Simms’ reconstruction, “towards the end Cumming is asked his opinion since he is the man on the ground. Cumming tells them straight….’As we speak the Croats are pitch-forking to death Muslim farmers in Prozor’. Douglas Hurd is incredulous and apparently says, ‘I don’t think we want to hear that’.”

The argument of safeguarding humanitarian effort

The second of Hurd’s stratagems was the attempt to use the argument of humanitarian concerns. Since all ‘sides’, ‘parties’, or ‘factions’ were more or less equally to blame, the only true victims could be the suffering population. Any sort of military action on behalf of the Bosnians – lifting the arms embargo and/or air strikes – risked ‘jeopardising the humanitarian aid effort’. This was repeatedly justified with reference to ‘expert’ advice’ and the pleas of ‘men on the ground’.

To rebut this, Simms quotes journalist Alec Russell, who visited the embattled Bosnian government enclave of Gorazde in the late summer of 1992. The closing words of the town’s commander to Russell were this: ‘Send a message to your governments, Thank them for their food and medicines. Tell them that at least we will die with full stomachs’.

In 1993 Britain had about 2000 troops in Bosnia as part of the UN force (UNPROFOR), tasked with the delivery and protection of international aid. Britain argued that if US or NATO air power was used, then it would be forced to evacuate these troops for their safety, and hence humanitarian aid effort on the ground would be affected. Britain even went so far as to claim that the Bosnian government would rather the UN remained rather than the embargo be lifted! Brendan Simms quotes a statement from Hurd in December 1994 that ‘when it came to the point in September, the Bosnian government did not want the immediate lifting of the arms embargo if that meant the withdrawal of UNPROFOR’. The reality of the matter is that the Bosnian government unswervingly demanded the repeal of the embargo from the very beginning to the very end of the war.

In September 1992, Douglas Hurd argued, “the difficulty with all the military options, is that in such a terrain, with the intermingling of military personnel and of civilians and of Serb, Bosnians and Croats, it is hard to work out a practical scheme which would not merely add to the number killed without ending the fighting”. However In 1992, spy satellite image analysis at the National Security Agency had noted Serb artillery around Sarajevo ‘was highly vulnerable to air attack’. Colonel Karl Lowe, a US military planner working in the area at the time also expressed his view that the Yugoslav People’s Army was vulnerable to such attack. The Chief of Staff of the US Air Force, General Merril McPeak, advised the White House throughout 1993 that the Bosnian Serbs could be checked through air power alone.

Bernard Simms damning indictment is that “the humanitarian operation had been intended as an ameliorative measure to fend off-US sponsored demands for military intervention”. So behind the pious pronouncements of humanitarian relief, the reality was that Britain had deployed troops in UNPROFOR specifically for the purpose of blocking any air attacks by the US or NATO on the Serbian positions!

Simms also notes, “the political purpose of the deployment was not stated, but quite transparent: to head off demands for a politico-military commitment to the Bosnian government by the pre-emptive dispatch of ground forces for purely humanitarian purposes”. He backs this conclusion by referring to Dr Robert Hunter, US ambassador to NATO, who ‘was convinced that one of the reasons the British had troops in UNPROFOR in relationship to bombing was you had troops on the ground, therefore you can’t bomb’.

The argument of Serb military prowess

Further disinformation put up by the British policy makers was the prowess of the Serbian army. This line was taken up by British officers in UNPROFOR, as noted above, but who went much further by acquiring a misplaced sense of camaraderie with Serb army officers.

Lord Owen in particular was fed wildly inaccurate assessments, which he then proceeded to pronounce with great confidence in interviews to the media and at EU meetings. In his memoir, ‘Balkan Oddesey’, Owen writes that he told EU foreign ministers that the Serbs could take Sarajevo anytime. Simms notes that in reality the Serbs had tried – and miserably failed – to rush Sarajevo at the outset of the conflict. They had no desire to engage with the enemy in street fighting, choosing instead to wear down the defenders through hunger and shelling.

Owen also held General Mladic in awe. ‘In one sense,’ he recalls in his memoir, ‘[Mladic] wanted a real fight, believing that picking off Muslims was beneath the dignity of the Serbs’. ‘Mladic was widely judged to have fought with considerable skill around Knin…. He never appeared afraid of NATO air strikes or US threats to lift the embargo. Probably he would have welcomed both as getting the politicians off his back and allowing him to wage war with the gloves off.’

Simms sets the record right:

“Of course, this was nonsense: Mladic made his reputation slaughtering lightly armed Croat national guardsmen and defenceless Muslims; and when it was clear that Nato meant business in 1995, he quickly folded.”

The most sinister effect of the policy makers’s decision to project Serb army strength was the impact on the British commanders serving with UNPROFOR. They not only toed the official line without exception, but accentuated the bias with an Islamophobic and racist streak. The spirit of bonhomie that emerged between General Rose and General Ratko Mladic is captured in the cover page photo of Brendan Simms’ book, where the pair are seen shaking hands over drinks. Simms writes that in the officers’ mess of one of the British commanders, the Bosnian Muslims were referred to as ‘the wogs’.

Lt. Col Riley, the CO of the Royal Welch Fusiliers at Gorazde, describes his meeting with Mladic in August 1995, after the Srebrenica massacre, in adulatory terms, “General Mladic is an imposing, indeed dominating, figure both physically and in terms of his personality; it was easy to see why his own men adore him and his enemies fear him. He in turn clearly knew what the Royal Welch had endured, and he was charm itself…. We then adjourned for some Serb hospitality: a magnificent lunch of barbecued lamb, with the inevitable deluge of plum brandy. I left with a signed photograph of the General”.

In the haze of Whitehall indoctrination and boozy Serb lunches, the British army command in Bosnia lost sight of two fundamental truths: the Bosnians were the principal victims of Serb aggression; the role of UNPROFOR was to be impartial.

General Rose’s lack of integrity is highlighted by the marketplace mortar attacks of February 1994 in Sarajevo, referred to previously. He spent much of 1994 suggesting or insinuating to journalists and visitors that the Bosnians were shelling themselves. This was precisely what the political masters in Whitehall wished to hear, to re-enforce their propaganda of the moral equivalence between the Bosnians and Serbs. Prestigious journals that ought to have known better, such as ‘Jane’s Defence Weekly’ repeated the canard that the marketplace massacre was self-inflicted to gain sympathy. Prior to relinquishing his UNPROFOR command in January 1995, General Rose had even threatened the Bosnian government forces around Sarajevo with air strikes after blaming them for renewed fighting. No small wonder he left bearing gifts from Mladic – two oil canvas paintings.

One of the most revealing sections of Simms’ remarkable book is the extent to which the British officers selected for duties in Bosnia had Serbophile tendencies. At least three of the British military interpreters or liaison officers were of Serb parentage. One of them, Captain Mike Stanley, or Milos Stankovic, was arrested and released on charges of spying for the Serbs. Simms also reveals the crude racist assessments of the Defence Intelligence Staff (DIS): the Serbs are ‘incorrigibly romantic’; the Croats ‘more sophisticated, self-possessed and urbane’; ‘the Serbs and Croats together consider the Muslims as second class citizens, untrustworthy, conspiratorial and disloyal’.

Milosovic’s trial will no doubt throw up titbits on British and French connivance with the Serbs. However the full story will probably be only known to the next generation, when the Public Record Office opens up the Foreign Office files. For the present, we are indebted to Brendan Simms for a salutory lesson on the culture of contemporary policy making elites. This account of how a government can claim the moral high ground in the pursuit of amoral policies is particularly apt for Muslim readers today.

M A Sherif