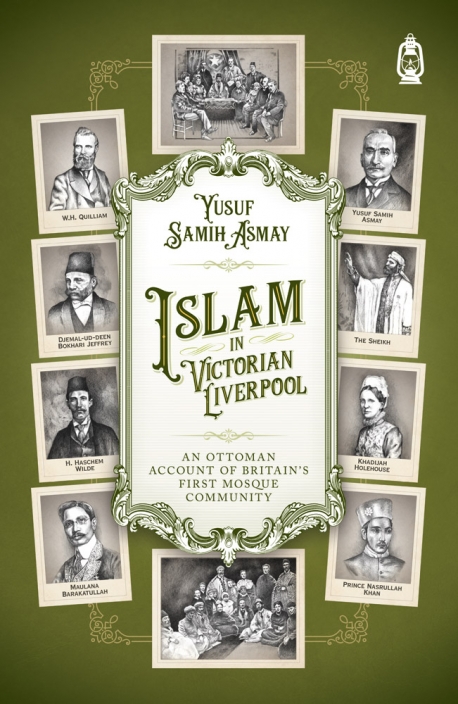

Author: Yusuf Samih Asmay

Editors: Yahya Birt, Riordan Macnamara, Münire Zeyneb Maksadoğlu.

Publisher: Claritas Books

Year: 2021

Pages: 162

ISBN: 978-1-80011-982-6

Source: https://www.claritasbooks.com/books/all-books/islam-in-victorian-liverpool

This is a welcome addition to the scholarship on the history of Muslims in Britain that adds significantly to what is known of Abdullah Quilliam and the Liverpool Muslim Institute (LMI) he founded in 1887. It is a translation of a 112-page travelogue written in Ottoman Turkish by Yusuf Samih Asmay, based on a two month encounter with Quilliam and the Liverpool Muslim community around July 1895. Asmay was a Turkish-language instructor posted to Cairo, where he also established a pro-Ottoman newspaper in 1889. It is an account rich in descriptive detail, such as the social milieu in Victorian England and the physical setting of the Institute at 8 Brougham Terrace. Astay was as much an investigative journalist as a travel writer and took upon himself to expose the weaknesses in Quilliam’s character and the religious practices with forensic precision. Islam in Victorian Liverpool is the first translation into English of Asmay’s account and the editors are to be commended for a perceptive introduction, appendices with translations of Ottoman documents and biographical sketches of the main individuals at LMI at the time.

Abdullah Quilliam (1856-1932) was an iconic figure for Muslims passing through British universities in the 1890s and early 1900s.They turned to him when in need, whether it be as a speaker for their events, helping in funeral arrangements or officiating a nikah. The columns of his journal, The Crescent, reported on their academic successes and even accomplishments on the playing field. Quilliam also went out of his way to care for down-and-out lascars in the Liverpool docks. With his small band, Quilliam stood up to Islamophobic abuse and boldly had the adhan called from the balcony at Brougham Terrace.

The editors of Islam in Victorian Liverpool rightly note the need for need for a ‘warts and all’ telling of British Muslim history, because it allows for “greater acuity and deeper self-understanding” in reflections on “questions of Muslim faith, identity and belonging in the West.” Quilliam was well-regarded across the Muslim world as a pioneer and defender of Muslim interests, but there were also puzzling aspects to his personality. Ron Geaves’s biography Islam in Victorian Britain, The Life and Times of Abdullah Quilliam (Kube Publishing, 2010) touched on this in a chapter entitled ‘A Mysterious Twilight’. This referred to Quilliam being struck off from his legal practice in 1908, the adoption of the persona of a Dr. Henri de Léon and his polygamous marriages. A later work on British Muslims by Jamie Gilham (Loyal Enemies, British Converts to Islam, 1850-1890, Hurst, 2014), similarly combined an appreciation of Quilliam’s contribution to Muslim institution-building but noted the “exaggerated claims about the number of converts”.

Asmay’s assessment is unequivocal. He clearly disliked the “attention seeking” Quilliam whose achievements were to be seen in the media “almost every day”. While “there is no licence to doubt the faith and Islam of the members” of the LMI, “Mr.Quilliam’s disposition is very strange from beginning to end”. The claims in Quilliam’s Crescent weekly of the Liverpool Muslim College at LMI were hollow: it was a single room where “they do not teach anything other than elementary sciences in English”. The LMI had adopted certain practices in worship “without consulting Islamic scholars or literature”. He witnessed “the convert sisters who play the piano, sing ballads and sometimes get up to do a few step dances”. The adhan was given at 7pm, irrespective of the actual times of prayer. Asmay’s most devastating criticisms relate to financial probity and immorality: “Mr. Quilliam has a regard for the fairer sex as much as he loves money, so he made a name for himself in Liverpool: they say that once he sets his eyes on a dove, she cannot escape his clutches even if she flies away.” Asmay set a high bar for anyone claiming to be a Muslim leader, “We Turks believe in the proverb that ‘A leader must be true in speech and true of heart’. I wonder if we can apply it in Mr. Quilliam’s case.”

Researchers will be grateful to the editors for bringing new biographical material on Maulvi Barkatullah Bhopali to light. It was known that Barkatullah had arrived in London in 1887, but his circumstances and terms of employment at LMI from 1893-1896 were obscure. Asmay documents his several conversations with this “young Indian, chestnut-hued, with a slim, trim build, bespectacled, [and] high spirited.” Barkatullah was in desperate financial straits before being offered employment by Quilliam, but his departure after three years were not on good terms.

In the Introduction, the editors touch on Asmay’s possible motivations for his critical assessments and conclude that he was not pursuing an anti-LMI agenda at the time of his visit in 1895. Quilliam was successful in having the book banned in Ottoman Turkey. This may have stopped wider publicity of misdeeds, but it is surprising that his contemporaries who would have known him first hand – and accepted him in his Dr Leon persona – continued to regard him with respect. For example, he presided at the meeting held at the Shah Jahan Mosque, Woking for the visiting Indian Khilafat delegation in March 1920, contributed learned articles to Islamic Culture in 1927-1930 when it was under Pickthall’s editorship, appears in the group photo, seated with his wife Edith Miriam Leon, at the reception, again at Woking, in honour of the sons of the Nizam of Hyderabad in 1931.

Through this effort, the editors and Claritas Books have demonstrated the importance of Ottoman archival sources in developing a more complete understanding, “warts and all” of British Muslim experiences in Victorian and Edwardian times. A request to Claritas for the next edition: please include an index!

Jamil Sherif, June 2023