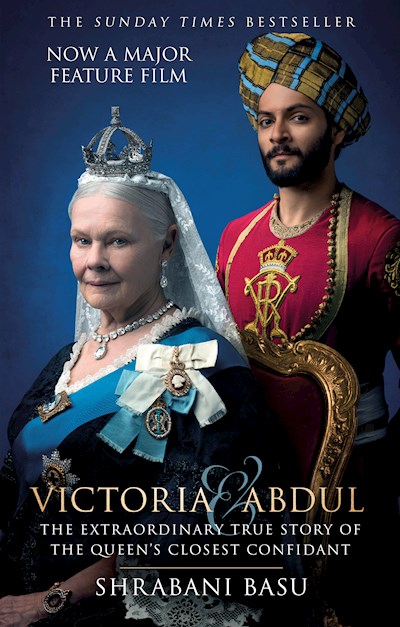

Author: Shrabani Basu

Publisher: The History Press, 2010

Source: https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/publication/victoria-and-abdul-film-tie-in/9780750982580/

On a summer day in 1886, in the forty-ninth year of Queen Victoria’s reign, destiny smiled on a young Indian Muslim working in a clerical post at the Central Jail, Agra. Of handsome bearing, reliable family background and aesthetic good sense, Abdul Karim had already impressed his English supervisor. Summoned to the superintendent’s office, Abdul Karim perhaps expected a commendation for his work in organising the preparation and collection of various artefacts, including a carpet prepared by the Agra inmates, for a recent exhibition in London. He did not have the slightest inkling of what lay ahead:

“During his [the supervisor’s] trip to London, the Queen had discussed the possibility of employing some Indian servants during the Jubilee. She was expecting a number of Indian Princes for the celebration and felt she could do with someone to help her address the Indians presented to her…he [the supervisor] then asked Karim if he would like to travel to England to be the Queen’s personal attendant and table hand during the Jubilee celebrations the following year”.

Thus began Karim’s fairytale exposure to Victoria’s court for fourteen years, during which he became one of her most trusted friends and elevated to the status of ‘munshi’ or the Queen’s teacher of Urdu and official Indian clerk, as well as being conferred with various honours such as the CIE (Companion of the Indian Empire) and the Star of India. Author Shrabani Basu provides a most evocative and perceptive account of the triangular relationships between a dignified Indian Muslim who remained true to his values and traditions, a lonely and intelligent Empress who disliked many of her immediate family members, and a racist and jealous Establishment.

The enduring image is of AbdulKarim’s sense of duty and Queen Victoria’s reciprocating appreciation. Shrabani Basu’s research has uncovered this description left by granddaughter Princess Marie of a visit to Windsor with her fiancé Prince Ferdinand:

“The young Princess recalled how the silence was broken by the click of the door handle and the tall figure of the Munshi who stood on the doorway. He was dressed in gold with a white turban. Without moving from the doorway, he raised ‘one honey-coloured hand to his heart, his lips and his forehead. He neither moved into the room nor spoke.’ The young couple could only stare at this vision in silk and gold. No one spoke for several minutes. The Queen – evidently pleased with the effect the Munshi had had – continued to smile. The Munshi remained standing at the door, manifesting, as young Marie said, ‘no emotion at all, simply waiting in Eastern dignity for those things that were to come to pass”.

This reserve and formality was dispelled when Victoria and Abdul Karim were alone, much of the time taken up in lessons in Urdu. Queen Victoria was an apt pupil, and by the end of her life could write in the script; Abdul Karim too learned English from her, and she would correct some of his grammatical errors. Basu provides a touching portrait:

“The Queen was a great letter writer. She liked to send written instructions to members of her Household and insisted that they write to her as well. All this meant a lot of paperwork for the Household, but they had no choice. She wrote regularly to the Viceroy, the Secretary of State for India and her extended family. Sitting at her desk – whether it was the brass-edged one in her sitting room which was always cluttered with innumerable trinkets, photos and memorabilia, or the field table in the gardens – the tiny figure of the elderly Queen could be seen writing endless letters on her black-lined notepaper, underlining words for emphasis. Her plump fingers would move agitatedly over the paper when she was angry or upset, the rings and bracelets that she always wore glittering as she worked late into the night. She would never go to bed without completing her boxes…helping her with her papers, Karim became a letter-writer himself. He wrote regularly to the Queen and never missed congratulating her for a happy event in her life. Sometimes he would send her an ode, composed by an Urdu poet in India. When he travelled to India, he wrote every day, updating her on all developments”.

In a letter to her daughter Vicky in 1890 the Queen wrote,

My good Abdul Karim’s departure is vv inconvenient as he looked after all my boxes – letters etc besides my lessons and I miss him terribly! 4 months is a long time; I have such interesting and instructive conversations with him about India – the people, customs and his religion…”

The Munshi maintained his religious practices – and no impediment was placed by his royal mistress – whether it be at Buckingham Palace, Balmoral or the royal residence Osborne House in the Isle of Wight. Shrabani Basu notes

“It was a custom with Karim and the Indian attendants that after the holy month of Ramadan – throughout which they would observe their strict fast – they would go to the Shah Jehan mosque in Woking to pray Id….the Birmingham Post observed in an article in May 1891 that other Muslims “from all parts of England would come to see the Munshi and join him in prayer”.

A cook in the royal kitchens recalled,

“For religious reasons, they [Munshi and other Muslims in the royal household] could not use the meat which came to the kitchens in the ordinary way, and so killed their own sheep and poultry for the curries [halal].”

When Munshi’s wife and mother-in-law joined him, the Queen in her munificence provided cottages at all her locations. A special cottage was built for him in the Balmoral Estate, which she named ‘Karim Cottage’ in his honour. The ladies of the house observed purdah, and in the words of the Court Circular in The Times in 1893, both ladies “were closely veiled…the oriental coverings completely concealing the features and figures of the wearers”. The Queen wrote “I went down with Ina McNeill [extra woman of the bedchamber] to see them. The Munshi’s wife wore a beautiful sari of crimson gauze. She is nice looking, but would not raise her eyes, she was so shy”.

In another remarkable letter the Queen wrote to the Munshi that she would like his wife to meet her daughter Vicky – Empress Frederick:

“My dear Abdul, the Empress wd much like to go – see your dear wife tomorrow (Friday) mg at a little past 12. She says she is sorry she shd trouble herself by dressing in smart clothes for her, but I know you wd like her to be seen in fine clothes. Only I think the large nose rings spoil her pretty young face, your loving mother, Victoria RI”.

The Queen would frequently begin her letters to Abdul Karim with “My dear good Abdul’, ending “God bless you. VRI”, as above, or even “Ever your truly devoted an fond loving mother, VRI”, and invariably signed in Urdu.

Munshi Abdul Karim provided the Queen with first-hand information on the British administration in India. Shrabani Basu handles this aspect with commendable lack of partisanship. He spoke to her about Hindu-Muslim disturbances during Muharram, in response to which Victoria wrote to the Viceroy Lord Lansdowne to take some extra measures so that the “Muslims could carry out their ceremonies “quietly and without molestation”. Another Viceroy would wonder how the Queen was under the impression that “many of our Residents [political advisors to Indian principalities] are rude and overbearing” and that “my own private opinion is that her Indian Munshi tells her that in India there is the greatest devotion to herself and all her family, but at the same time distrust and dislike of the Government”.

There was to be an inevitable collision course between the favoured Indian Muslim courtier and the Establishment. The author chronicles the mounting hatred of the Royal Household and aristocratic circles towards the Munshi. Sir Henry Ponsonby, the Queen’s private secretary and head of the Household, writing to the royal physician, Dr Reid, stated that “the advance of the Black Brigade is a serious nuisance”. The Queen’s maid of honour, Marie Mallet, was equally irritated, “I am for ever meeting him in the passages or the garden or face to face on the stairs and each time I shudder”. When Munshi’s mother-in-law fell ill the royal physician who was asked to tend to her commented that every time he visited the Munshi’s house, “a different tongue would be stuck out to him from behind the purdah”. Foremost in the fray against Munshi was the Prince of Wales, ‘Bertie’, later Edward VII, who bided his time for the moment he was King. He then acted with utter malice in January 1901, catching the Munshi unawares in his cottage on the Windsor estate:

“But only days after the Queen’s death the Munshi was woken by the sound of loud banging on his door…the King had ordered a raid on his house, demanding he hand over all the letters Victoria had written to him. The Munshi, his wife and nephew watched in horror as the letters …were torn from his desk and cast into a bonfire…The King wanted no trace left of the relationship between his mother and the Munshi. Abdul Karim the Queen’s companion and teacher for thirteen years, was ordered to leave the country and packed his bags like a common criminal. All the other Indian servants were also asked to go home….The new King did not want to see any more turbans in the palaces or smell of curries from the Royal kitchens. The Edwardian era had begun”.

The Munshi returned to his estate near Agra, passing away the time “riding in his carriage to MacDonald Park, sitting by the statue of Queen Victoria and watching the sunset over the Taj Mahal”. He died in 1909 and his descendents migrated to Pakistan after the Partition. As far as future generations in Britain were concerned, while much is known about Victoria, the fact that her dearest friend had been a Muslim from India who practiced his faith in the royal palaces is unmentioned. Shrabani Basu’s warm recollection ought to rectify this lacuna in the collective memory.

Edward VII’s private resentments were to subsequently surface in more public displays of antipathy. He actively supported the cessation of Crete from the Ottoman Empire to Greece in 1908, also backing the Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia Herzegovina. Wilfred Scawen Blunt in his Diaries noted on the King’s death in 1910, “his only notable failure was in the affair of Bosnia, and people in England knew little of the conditions to understand how great a failure it was”. [W S Blunt, My Diaries, v2, 1900-1914, Martin Secker; p.321] Amongst the Munshi’s Muslim friends during his British sojourn was Maulvi Rafiuddin Ahmed, nicknamed ‘Ruffian’ by the snobs at Court. In reality Rafiuddin was an accomplished law student, writer and public speaker called to the Bar in 1892. Rafiuddin immersed himself in a variety of Muslim associations of the day, including the Anjuman-e-Islam, the first collective effort of Muslims in Britain seeking to represent Islam and Muslim interests in the Empire’s capital city. Munshi introduced Rafiuddin to the Queen, who, impressed with his abilities and contacts, sent him abroad on a diplomatic mission to the Ottoman court. Maulvi Rafiuddin was also an associate of Abdullah Quilliam of Liverpool, the subject of Professor Geaves’s absorbing biography Islam in Victorian Britain, The Life and Times of Abdullah Quilliam Other than the Rafiuddin connection, Munshi and Quilliam were two very different Muslims of the Victorian era – one the personification of proprietary, the other more like a daring stallion requiring restraint.