An exemplary life dedicated to defending the honour of Islam, promoting Muslim unity and fostering wider understanding based on civility and morality.

In the passing away of Hashir Faruqi in London on 11 January 2022, Muslims in Britain and across the world have lost a wise, well-informed counsellor who was an inspiring role model for his selflessness and dedicated service to Islamic causes.

He was a scientist of Pakistani heritage who found his vocation as a journalist and community activist after settling in London in 1963. He was a trustee and guiding figure in civil society initiatives that gave British Muslims a voice in the public space, including the London Islamic Circle, the UK Islamic Mission, the Islamic Foundation, Leicester, the relief charity Muslim Aid and the Muslim Council of Britain. He founded the bi-monthly journal Impact International in 1971 to provide news and analyses on Muslim affairs, while also offering a moral steer based on Islamic values. He believed that the Muslim world would not be able to shake itself of neo-colonialism unless it independently managed its information channels and news collection.

He outlined his credo for British Muslims in the wake of The Satanic Verses saga in its issue published in September 1990,

Muslims in Britain are British citizens. They also form part of a world community, the Umma, and they cannot remain unaffected by whatever happens within or without the Umma. To be fair this universal outlook and response is not exclusive to Muslims alone. It applied to every sensitive sole who lived in our global village. Where Muslims should try to compete and excel is the fairness of their outlook and approach. There is no position in Islam of ‘my Muslim right or wrong’. However, one does ‘help’ a Muslim when he is wrong: by helping him out of it. But Muslims cannot seek justification for their own excesses on the ground that others had committed excesses against them. Therefore, as long as Muslims follow the universal and unilateral standards of Islam there can be no conflict between being British and being a member of a world moral community. [Impact International, 14-27 September 1990]

His early years were in pre-partition India in the UP (United Provinces, later Uttar Pradesh). He completed a BSc at the Kanpur Agricultural College, here he was secretary of the Muslim Students Union and its Urdu literary society. In 1953, he migrated to Pakistan and worked as an entomologist at the Ministry of Agriculture. He was on deputation to Saudi Arabia for a year and later proceeded to Imperial College, London on a Colombo Plan scholarship for research into locust control.

On arrival in Britain, he joined the activities of the UK Islamic Mission (UKIM), an association of Muslims from the sub-continent in existence since 1962. Its activities were aligned to his own understanding of Islam as a comprehensive way of life addressing needs of the individual and society, as elaborated by the twentieth century reformer Abul A’Ala Maududi. Hashir Faruqi’s first publishing venture, to produce a newsletter during the Indo-Pakistan War of 1965 to correct a perceived pro-India bias in British media, was not successful but provided valuable experience for Impact International later.

Two events led him to abandon a scientific career and devote himself fully to media monitoring and community activism: the trial and eventual hanging of Sayyid Qutb in 1966 and the debacle of the Six-Day War of 1967. He organised a committee at the UKIM offices in Angel to alert Muslim embassies to Qutb’s sentence. A quartet of like-minded colleagues – Faruqi, Ebrahimsa Mohamed, a law student from Malaysia, AbdulWahid Hamid, from Trinidad, completing a Master’s degree at the School of Oriental & African Studies, and Abdullah Jibril Oyekan, soon to become the first Nigerian with a doctorate in Chemical Engineering from Imperial College – were the leading lights of the London Islamic Circle which met weekly in the library of Regent’s Lodge, the original Islamic Cultural Centre. It was a pan-Islamic forum that brought together Muslims in a congenial social setting to discuss current affairs and benefit from lectures on Islamic topics. He also wrote for the Review of Books & Articles, a Gestetner machine-printed publication of the London Islamic Circle.

Faruqi was a regular contributor to The Muslim, the monthly journal the Federation of Islamic Societies (FOSIS) under the pen names ‘Scribe’ and ‘A.Irfan’ from 1967. He would highlight news not on the radar of Western media. His pen was sharpest when writing about despots and their actions. As a conversationalist he could draw out both the young and old, and these experiences sometimes found their way in his columns, “The other day I was speaking to a Muslim child, about 8 and brought up in a reasonably good Muslim home. He was trying to draw something. I took his crayons and sketched a mosque – dome, minarets and all. I asked him what it was? ‘A birthday cake’, came the quick reply.”

As someone who had migrated from Hindustan, he felt deeply for its Muslims and was prescient in this assessment published in the November 1969 issue of The Muslim,

Last September witnessed one of the worst disasters for Muslims in Ahmedabad, India. Eight thousand were massacred, many more seriously injured, millions worth of property destroyed, mosques desecrated, and institutions pillaged. It is no use going into gruesome details of how pregnant ladies were knifed, children butchered before the eyes of their parents, women molested, and whole families roasted alive in fire . . . ostensibly, the Muslims of Gujrat were insolent enough to chase away the herd of cows brought in the path of some procession being taken out by them. But even if there were no cows, that would be not mean the end of the excuse. These disturbances have a definite and cyclic patter and have become very much part of the Indian social behaviour . . . Muslims are non-citizens de facto. The pretences and platitudes of the constitution are nowhere to be found in the actualities of the situation. Apart from the show-boys, stooges and figureheads, the entire political, legislative and administrative machinery has been gradually denuded of any effective representation or participation in so far as the Muslims are concerned . . . the indifferent attitude, however of the world Muslim community, particularly are the Arab regimes, is to say the least callous and shameful.

He admired Muhammad Ali Jinnah and often reminded readers of Impact of the motivations that led to the establishment of Pakistan – but Jinnah was, “indeed a great leader but not the owner of its vision. The vision belonged to the 100 million Muslims of the then British India who had no doubts or confusion about their Islamic destiny” [Impact International, September 2001].

His small flat in Kilburn became an essential stopping point for scholars, poets and activists from across the world. Friends will long remember these salons – such as the evening with the famous composer of naaths, Mahirul Qadri, or the ease with which he and friends would slip into an impromptu mushaira. Many a visitor enjoyed his home cooking, with meals served on a table brought out of the kitchen. One memorable occasion for this writer was the luncheon for the historian Hamid Algar in 1969, in the company of Professor Khurshid Ahmed. The conversation turned to Hashir Faruqi’s plans to launch a Muslim news magazine, and Professor Khurshid’s vision of a research centre on Islamic thought and practice in Leicester, where at the time he was pursuing doctoral studies. It is bold visionaries who can translate ideas to realities.

Hashir Faruqi’s name will forever be associated with Impact International, the bi-weekly (later monthly) that he launched in London in May 1971, as

a newspaper which seeks to interpret the ethos of the Muslim world; [provide] balanced reporting and analysis on education, society, economics and politics; book reviews, briefings and other special features.

It filled the gap that had been left when the Woking-based Islamic Review and Muslimnews International had ceased publication. There was a hunger in the English-reading Muslim public worldwide for news and analysis from an independent, Muslim perspective. Taking stock of the journal thirty-one years later he noted that its fundamental objectives had remained unchanged. These were to

promote the understanding of Islam and Muslims; set forth the broad Muslim point of view on religion, society, politics, and current affairs; raise general awareness of Islamic issues and Muslim concerns; help the process of informed policy-making, particularly in the Muslim societies and communities around the world, and advance a two-way understanding and mutuality between the Muslim and non-Muslim peoples, especially between the so-called Islamic and western worlds – on the basis of righteousness and civility. [Impact International, October 2002].

It was the stable where many aspiring writers cut their teeth, benefitting from his ideas and guidance. The image in the minds of many who saw him at work in the offices of Impact in Finsbury Park will remain of a thoughtful man with a ready smile, loyal to his tweed jacket, a cup of carefully prepared tea at hand, with pens and pencils sticking out of a side pocket, behind a desk piled with newspapers where he had marked the cuttings to be filed away for future reference. It was run on a shoe-string budget at much personal sacrifice. By this time, he was joined by his wife, Fakhra Begum, and four young children, in the same flat in Kilburn. Faruqi received a lucrative offer from a Saudi publisher to close down Impact and work for his journal at a London journalist’s salary commensurate with his talent and experience. He refused, preferring to maintain his integrity and live frugally. At the outset it was a simple 16-page publication. In an obituary of his friend, M. Ashiq Ashgar, Faruqi described the early days,

By the end of 1969, we were looking for an office, easy to reach by public transport and, quite frankly, as inexpensive as possible. Ashiq Asghar not only offered a two-floor space at the premises he owned – 33 Stroud Green Road – but in a sense forced us to move in and forced the pace upon us to bring out the magazine as soon as possible. It took brother AbdulWahid Hamid (the writer and scholar) and his brother, AbdulAhad, another few months, to do up the place, filling the cracks with Polyfiller, papering the walls, painting the doors and windows, thus giving it the looks of an office. The doing-up took that long because the volunteers, AbdulWahid and his brother, could only do something during the evenings and weekends. After he had finally cleaned his hands off the paint and glue and taken off his apron, AbdulWahid sat on an old second-hand chair and desk as associate editor. Such is the modest history of impact, and Ashiq Asghar was part of this struggling history. The rent was modest and payment at leisure. [Impact, April 2003]”.

Some years later, Impact relocated to a shed at the Muslim Welfare House, adjacent to Finsbury Park underground. Faruqi also built up a network of contributors and reporters across the world who believed in the cause and did not seek any monetary recompense for filing stories

The launch of Impact could not have been more timely given the news interest in the secession movement in East Pakistan and the rapid judgement in the West in its favour. The first issue, published in May 1971, quoted the “undisclosed glee” with which events were anticipated by the Sunday Telegraph, that “the militant faith of Islam, having achieved more than 1300 years after the death of the Prophet its most formidable political expression ever [i.e. Pakistan founded as an Islamic Republic] is yielding to simple nationalism . . . is approaching its inevitable end.” Faruqi believed in maintaining a united Pakistan and called for an “adult attitude” so that both West and East Pakistanis should take stock of what had gone wrong. There was discontent in both wings and time was for unity and understanding. Faruqi revealed the role played by Maulana Bashani in shoring up the Ayub Khan regime during the elections held in 1964-65, thus an opportunity to bring a democratic order was lost. As a civil war unfolded, Impact was a unique source of information for providing data on the atrocities committed by the Pakistan army as well as the secessionists.

His travels allowed him to obtain unique access to forums of world Muslim leaders. His interviewing technique was precise. Many an important Muslim politician emerged from the experience with the sense of having been delicately dissected by a mosquito! Well into an interview with General Ziaul Haq of Pakistan, he sprang the question “What is your constituency?”. The response: My constituency, which is the military constituency”.

Among the leaders he liked and admired was Tunku Abdur Rahman, first Secretary General of the Islamic Secretariat (later OIC, Organisation for Islamic Cooperation) and Necmettin Erbakan, Prime Minister of Turkey.

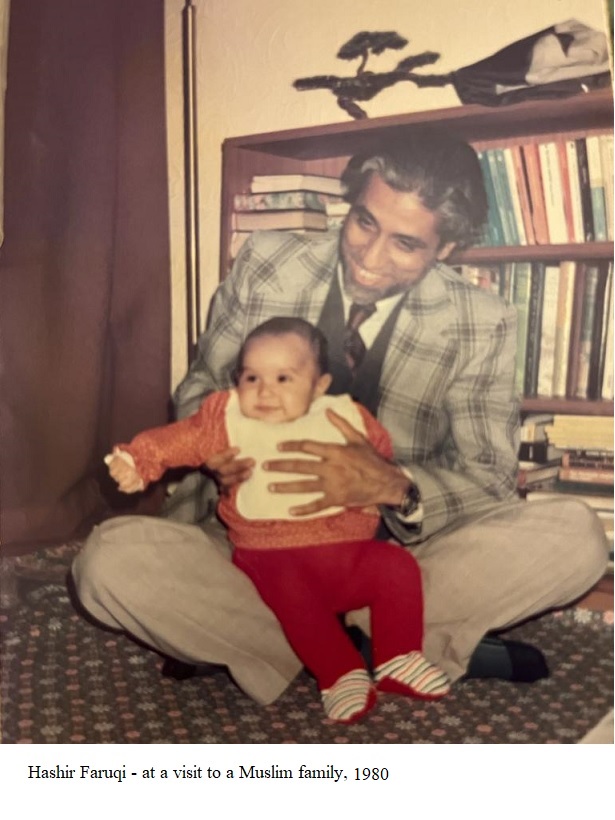

There was one occasion when Faruqi was in the news rather than reporting or analysing it: this was the Iranian Embassy siege in 1980, where he was among the hostages. Accounts written about those dangerous days refer to his attempts to find ways for ending the saga peacefully and coolness under fire.

Faruqi could not remain silent on the publication of the sacrilegious The Satanic Verses in 1988. For Iqbal (now Sir) Sacranie, at the time secretary of Balham Mosque was at a community meeting in September 1988, Faruqi played a decisive role,

I vividly remember his passionate plea and appeal to heads of organisations and activists who had come from different parts of the country to come together on one platform and deal with the serious crisis arising from the publication. He emphasised that with hikmah [wisdom], and at all times respecting the laws of the country, we will achieve our goal. I was impressed with his sensible reasoning to pursue a well-coordinated and dignified campaign to bring about the changes in legislation and more importantly a fair perspective in the mainstream media. Hashir Faruqi ‘s role in the formation of an ad hoc umbrella body, UK Action Committee on Islamic Affairs ( UKACIA) to coordinate responses was pivotal . . . He was the voice of reason when tempers ran high due to frustration over lack of action on the part of government and the media. I recall he would emphasise the need for humility when I argued that we need to use strong language in our Press Releases. He used to remind constantly the responsibilities of the author and publisher. To write filth is the prerogative of any person but to publish filth is to give platform to propagate filth. Our campaign was not directed against the author but the publisher Penguin.

It was also at his suggestion that UKACIA adopted a collegiate approach by assigning leadership responsibilities to number of ‘convenors’.

Those unwilling to purchase the book were able to read extracts in the October 1988 issue of Impact in its cover story ‘Sacrilege – literary but filthy’. While Faruqi battled with the liberal establishment against the book, he did not join any of the calls for violence. In his analysis,

Instead of showing any understanding, the Muslim feeling of hurt was variously seen as the rise of Islamic militantism orchestrated by Libya, Saudi Arabia and Iran, as a reaction of insecurity by people caught in a climate of modernity and change, as a melancholy desire to escape into the dark ages and as a refusal to integrate with the British way of life. Neither was true.

After the book burning incident in Bradford, Kenneth Baker MP, Secretary of State for Education and Science at the time, scolded Muslims for their apparent intolerance in an article ‘Argument before Arson’ published in The Times of 30 January 1989. Faruqi responded in an open letter that was forthright in standing up for the community,

. . . You seem to have taken in by the media’s over-exaggerated blow up of the isolated incident when someone chose to draw attention to his feelings to an otherwise insensitive and censorious media by, in our view, unnecessarily, burning his own hard-earned £12.95. No-one had done it before, nor anyone else is going to adopt it as a standard method of demonstrating protest. Over 15,000 Muslims had marched in London 14 days after the Bradford ‘arson’ and two days before your article was written in order to express their pain and agony. It was a dignified and peaceful demonstrations sans arson and it would have been very constructive to have based your counsels on something much more wider and general that having to pick on a single instance . . . You have condemned and sentenced a whole community without giving it a hearing or without informing yourself of its case . . . In raising their objections to The Satanic Verses, Muslims are only trying to underscore the difference between the sacred and the profane, between tolerance and imposition, and, to use your on words, between ‘liberty and license’. ” [Impact International, February 1989].

Faruqi could write objectively and forcefully on what mattered to British Muslims and set the tone for how British Muslims could engage with government ministers.

Hashir Faruqi always had a serious side, but was also congenial company for a younger generation of British Muslims, who were befriended both by him and Fakhra Begum. He would cross-examine young visitors on their education and even suggest courses for higher studies!

By the mid-1990s, the networks formed during the Satanic Verses saga and anxieties with the genocide carried out by the Serbs against Bosnian Muslims prompted moves to establish an umbrella representative body for Muslims in Britain. Faruqi’s counsel was sought during the preparatory stages of the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB), inaugurated in November 1998. It was at his suggestion that a constitutional formula was devised that brought in the existing national organisations as stake-holders in the new venture. Iqbal Sacranie, the founding Secretary General recalls,

His vision for an umbrella body and its role for the future of British Muslims was shared widely. The intellectual ability to converse with cross section of our community was remarkable. He made it clear that we are not to be seen as a religious body issuing fatwas but more of a community organisation working on the lowest common denominator for the Common Good. He emphasised on achieving consensus which can be tiresome and frustrating but successful in the long run.

In 2003 he was among the welcoming committee that organised HRH The Prince of Wales’s visit to the Islamic Foundation, Markfield, and presented a token of appreciation to the royal visitor on behalf of its trustees. In 2013, Hashir Faruqi was recipient of the Editor’s Lifetime Achievement award at the Muslim News Award ceremony.

He shared with Professor Muhammad Hamidullah a disdain of Islamic work for worldly gain. When Hamidullah was conferred a civilian honour in Pakistan, he turned down the accompanying cash award, saying, “if I take it [credit] here, what would I get there [in the Hereafter]”. It summed up Faruqi Sahib’s life principle as well.

Kullu nafsin zai’qatul mauth. Inna lillah wa inna ilayhi rajiun.

- Muhammad Hashir Faruqi, journalist and British Muslim leader, born 4 January 1930; died 11 January 2022. His wife, Fakhra Begum, pre-deceased him. He is survived by his daughter Sadia, and sons Ausaf, Rafay and Irfan.