Author: Jean-Marie Blas De Roblès and Claude Sintès, translated into English and revised by Philip Kenrick

Publisher: The Society for Libyan Studies

Year: 2019

Pages: 314

ISBN: 9781900971546

Source: https://www.societyforlibyanstudies.org/shop/silphium-press/classical-antiquities-of-algeria/

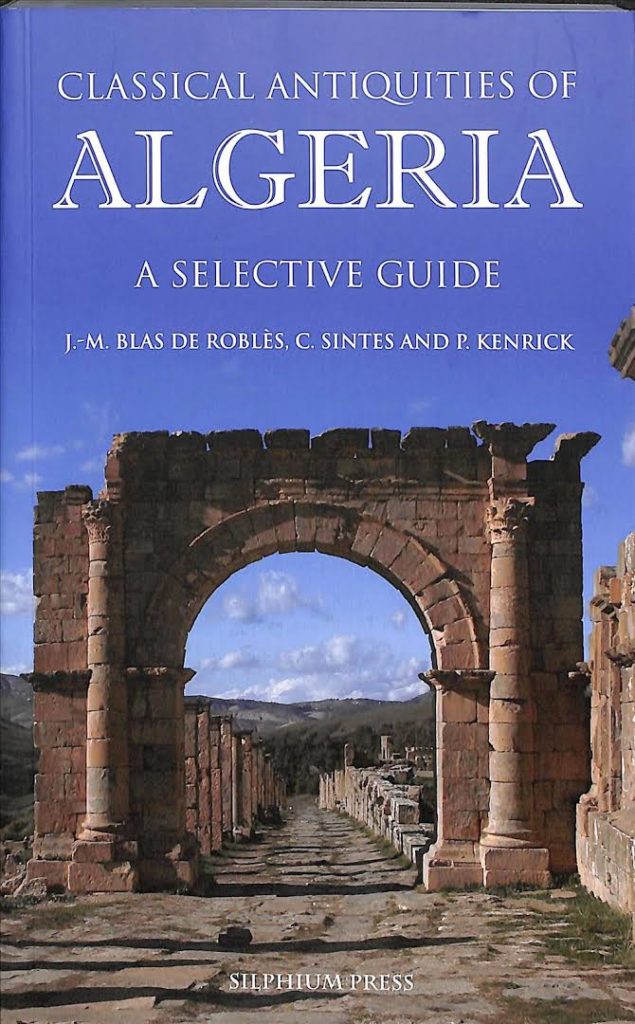

This is an invaluable guide to museums and archaeological sites in the beautiful land of Algeria, with a focus on the periods when it was part of the Roman empire, from around 100 BC and ending prior to the advent of Islam. It traces the fall of the native Phoenicians to the invading Romans, the incursions of Vandals and the Byzantine forces, and Christianity’s struggle in establishing a foothold in a society when chapels co-existed with altars to Apollo and Saturn. The guidebook is well-illustrated, with maps and photographs that allow a juxtaposition of the settlements of antiquity with today’s topography and towns. It is a revised, English version of Sites et monuments antiques de L’Algérie originally published in 2003.

The guide book has marvelous descriptions of the major Roman settlements and usefully provides today’s place names that would be invaluable in planning an itinerary, for example: Casearea – Cherchel; Sitifis – Sétif; Cirta – Constantine; Theveste -Tébessa; Hippo Regius – Bône/Annaba.

A typical example are the 18 pages devoted to Hippo Regius, the town where St. Augustine served as bishop in the Fourth Century AD. The section has two maps indicating the relationship of the site of Hippo with modern Annaba and the general layout during Roman times on the banks of the River Seybouse. The authors also provide a history trail when exploring the site, with numerous photographs of preserved ruins of the forum, marketplace and the baths, and various murals. The descriptions of Hippo Regius are of a pleasant setting, “with a particularly well sheltered bay, fresh water in profusion, a rich hinterland [. . .] the point of departure of ships carrying the Annona, the corn supply for the city of Rome”. Despite the passage of the millennia, the area seems to have an unchanging essence. Writing in the 1930s, the Algerian thinker Malek Bennabi has an evocative description of a train journey in the spring season, “when the orchard are in bloom, the breeze sweeps the landscape and the scent of rose bushes and the blossom of orange trees hangs over the plain to Bône.”

The authors are not shy of connecting past and present. There is much material on the schisms amongst the Christians, between the non-Trinitarian Donatists, the Catholic bishops and cults such as the circumcelliones

This movement (possibly deriving its name from ‘those who hand around the granaries’ – circum cellas – i.e. seasonal workers) seems to have sprung from the poor who worked on the country estates. Forming themselves into roving bands, these exploited people took advantage of the religious struggles between the Donatists and the Catholics to hold landlords to ransom, to humiliate or mistreat members of the Catholic clergy and to ravage the countryside with blood and fire. These ‘soldiers of Christ’ (as they called themselves) were sometimes encouraged or even instructed by the Donatist bishops. Mystics to the point of suicide, they accompanied their attacks with cries of Deo laudes (‘Praise the Lord’, in the same manner as has been heard more recently in another tongue, ‘Allahu akbar’).

The city of Constantine in eastern Algerian takes its name from the Emperor Constantine. Though wavering between the Donatists and Catholicism most of his life, he was responsible for summoning the First Council of Nicea in 325 at which the Christian creed as we know it today was promulgated.

A visit to the museum in Sétif is recommended, with the helpful note, “beware of the very shallow steps, one set of either side of the building, in the long display galleries!” There are several “masterpieces” to be viewed, such as the fourth century mural Indian triumph of Dionysus depicting Roman imperial pomp and glory, with chained slaves in the background. Sétif was the scene of a different type of barbarity in May 1945, when the French army massacred thousands of its inhabitants.

The guide notes the interrelationship between power and archaeology,

It was the [French] military which began to record the archaeological riches of the country. Many officers, educated in the Classical tradition, found this a pleasant way to pass the time [. . .] other motivations may be detected in the political wish to find a symbolic justification for the presence of the French. Rome and its heritage – pacification and civilisation of tribes described as ‘retarded’ – are never far from their discourse and statements of intent [. . .]

Military and scientific interests were intertwined, sometimes so closely that the despatch of General Négrier on taking of Tébessa gives an account not only on the movements of his troops but also of the antiquities visible in the captured town. This activity was not always documented as one would have wished, when irreparable destruction was carried out to build barracks on ancient sites which offered ‘an immense quantity of ancient material, ideally suited to new constructions.

When working in Hippo Regius, “the principal excavator, E. Marec, typically sought to expose the vestiges of the classical period and swept away any overlying traces of early medieval occupation without record”. The French marginalised and even obliterated the archaeology of the later periods of Muslim rule in Algeria, such as the Berber Rustamids, Zirids and Almoravids from the Ninth to Eleventh Century, in order to excavate underlying buildings. The British Empire was not dissimilar in its cavalier treatment of historical artefacts: the bricks from the ancient town of Harappa were used to build the railway lines through Sind! It is a tribute to Muslim respect for heritage that in the period Algeria was an Ottoman wilaya from 1515 to 1830, past relics were preserved.

This English edition of Sites et monuments antiques de L’Algérie, is an enhancement on the French original with updates, including Philip Kenrick’s site visits in February 2018. In a recent article in the journal Libyan Studies, he noted the “desperate paucity of any sort of decent written material in Arabic which might encourage the Libyan population itself to learn and respect its cultural heritage.” This applies to the Maghreb generally. The Society for Libyan Studies is to be commended for supporting this venture.

Jamil Sherif, July 2020