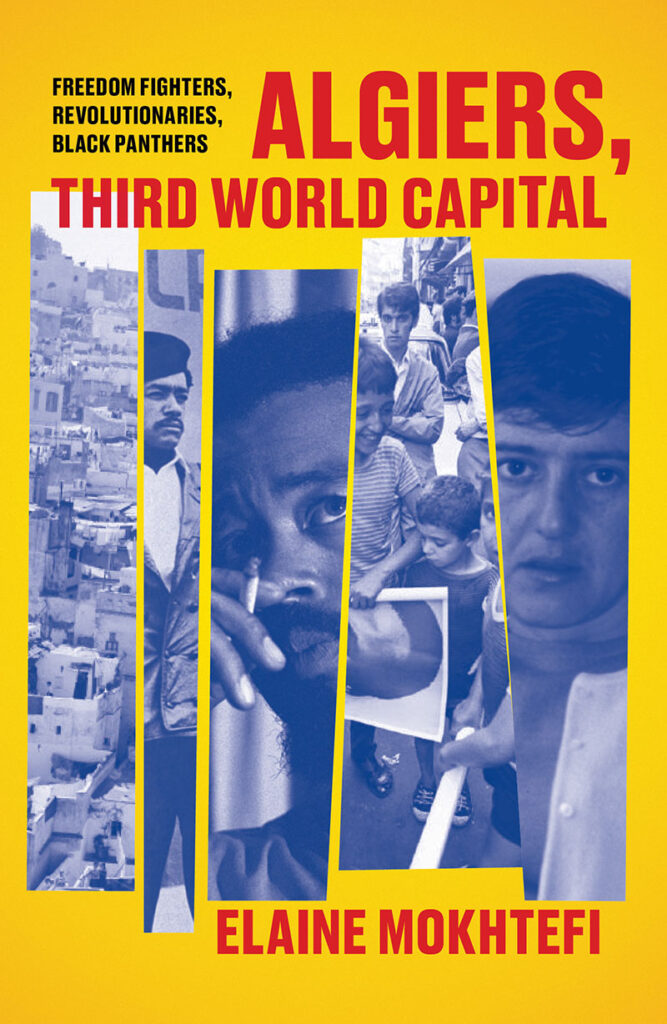

Authors: Elaine Mokhtefi

Publisher: Verso

Year: 2018

Pages: 242

ISBN: 781788730006

Source: https://www.versobooks.com/books/3027-algiers-third-world-capital

Elaine Mokhtefi’s memoir is a rich exposé of events during the anti-colonialist struggles of the 1960s and 70s, with impressions of its leading personalities, particularly those involved in the Algerian liberation movement. A central feature is a fly-on-the-wall account of what happened to the Black Panthers leadership after it fled the US for Algeria.

At a time when the Black Lives Movement has resulted in world-wide action to address colour racism, sections of this memoir make poignant reading. Malcolm X’s legacy is now keenly felt, and there is a greater awareness of the attempts to “exorcize him from the national past and the nation’s future” – as aptly put by Sohail Daulatzai in his The Black International and Black Freedom beyond America. Those who could have taken up the baton of leadership did not live up to Malcolm’s model. Perhaps this is what his assassins in 1965 intended, but the cause of Afro-American freedom and justice was set back for decades.

Elaine was born in Long Island in 1928, the only daughter of Charlie and Mildred Klein. The family led an itinerant life, with Charlie trying his hand running various small shops, finally settling in Connecticut where Elaine had to contend with anti-Semitism at the local public school. Even as a teenager, “my ideas about race, national origin and religion intensified with time to become political statements. At their core is a trait I could only have inherited from my mother, who treated every human being in the same warm, unprejudiced way.” A natural impulse to help others in need remained for life and emerge in the many actions described in this memoir. It is by no means a self-serving narrative, but a candid account by a white, female, New Yorker who backed the anti-colonialist cause and whose sense of adventure together with communication skills placed her at the heart of historic events. She was a confidante of disparate personalities such as Frantz Fanon, Stokely Carmichael and Eldridge Cleaver.

Elaine moved from New York to the Deep South at the age of sixteen when she enrolled at a women’s college in Georgia, but her rebelliousness led to an early exit. The next educational stop, in 1946, was the Latin American Institute in Manhattan for a Spanish language course:

One day they brought a speaker from the world-government-movement who talked about peace, democracy, and justice on a global scale . . . the world government meeting, in a matter of minutes, had propelled me into the future. I saw myself marching for peace, joining the battle for freedom from war and injustice. Suddenly, I had an ideal that coincided with my time of life and the historical moment.

It was good fortune to find an inspiring mission and project at an early stage of life.

Elaine’s activities placed her on the wrong side of the US establishment in 1953. By then she had worked for some years in Paris and was also fluent in French. Her copy book was marred by attendance at the World Assembly of Youth (WAY) congress, where she had stood up and questioned the exclusion of youth delegations from the Communist bloc. This, and her references to the racism endured by Afro-Americans, was noted by the FBI. When she applied for a job at the UN as an American citizen, her clearance document was rejected. She by-passed this bar by taking up a translator’s post at UNESCO through the Tunisian delegation. She notes,

The Algerian war became the defining issue of the 1950s in Europe. Everyone took sides, and wherever I lived – in France, Switzerland and Belgium – I became involved, marching in anti-war demonstrations, attending international meetings and discussions, introducing resolutions, denouncing torture. I met Algerian militants and representatives along the road at every stop.

These contacts led to an appointment at the Algerian office based in New York, that lobbied at the United Nations on behalf of the Algerian resistance. It worked from a converted apartment near the UN building, and again thanks to Tunisian intervention, Elaine was able to obtain an access pass. She offers a warm resume of the Algerian character: “I felt comfortable with the Algerians. They were dedicated, affectionate, and generous combatants. I dug their sensitivity. Like them, I saw myself as an American, not as Jewish American nor as an American Jew.” The memoir has many references to Franz Fanon,

In December 1958, Fanon headed the Algerian delegation to the All-African People’s Conference in Accra, a short-lived but powerful organisation. It was there he met and developed close relationships with Patrice Lumumba from the Congo, Holden Roberto (alias Rui Ventura) of Angola, and Félix Moumié of Cameroon . . . in August 1960, I was walking across the university campus in Accra on my way to the assembly hall and was stopped by a group of four men, three of whom were dressed in dark wool suits and ties; they looked stifled and incongruous under the tropical African sun. The fourth man, Fanon, was wearing light-coloured pants and a short-sleeve white shirt, with his jacket under his arm an no tie. He stepped forward and in basic English asked where the World Assembly of Youth congress was taking place. I caught the accent and responded in French, leading the way. He and I spoke, making a connection immediately. He told me later that his first thought was that I was French. When he realised I was not, he was relieved: we could empathize.

A threesome comprising Frantz Fanon, Mohamed Sahnoun, the Algerian student delegate, and herself worked at this Accra meeting to convince delegations to support resolutions against racism and colonialism. She notes of Fanon,

He once asked me what I wanted in a relationship. When I answered, “To put my head on someone’s shoulder,” he was adamant: Non, non, non: stay upright on your own two feet and keep moving forward to goals of your own.” His words would come back to me often, and I have repeated them to others in need of that advice, as I was at the time.”

Elaine was close at hand when Fanon was dying of leukaemia in 1961 in a Washington hospital. She cared for his six year old son Olivier at her own apartment in New York – which she shared with Mohamed Sahnoun – as well as widow Josie after Fanon passed away.

Algeria shook off French rule in July 1962. Elaine landed in Algiers three months later:

. . . within a matter of days, I knew I was in Algiers for the long term. The experiment to create a new socialist country from the impoverished colony, the tremendous task of building a state respected in the international arena, was daunting. My gut told me that I would settle there, whatever my future with Mohamed [Sahnoun]. I would have to find living quarters and a job.

The job was assistant to the press and information advisor to President Ben Bella, with responsibility for receiving and briefing foreign journalists. She had a grandstand view of the early days of Ben Bella’s presidency,

The great master of improvisation, Ben Bella, also became its slave and victim. He launched new national projects every day, but neglected the measures required to implement them; he created offices and agencies and committees that functioned in name only. Agrarian reform, infrastructure, economic development, housing programs were announced in glowing terms to a beguiled population but rarely saw the light of day. Faced with opposition or conflict, he either caved or strong-armed. One by one, revered leaders of the revolution were dismissed, or resigned. He turned to lesser personalities, made bargains, created parallel political structures. He ordered arrests and allowed torture. Ben Bella was popular, he was eloquent, he was attractive; but he had little education, and was overly conscious of his image . . .it was well known that the last person to get his ear usually came away with the prize.

By 1964, Elaine separated from Sahoun– he was now the Algerian ambassador to France. She took up a post in the government’s national press agency, Algérie Presse Service (APS), and four years later, Radio-Télévision Algérienne, (RTA). She lived in Algiers’ casbah and befriended many of the heroic women who had faced up to the French forces, such as Nassima Hablal, who had been tortured by the French military at the infamous Villa Susini. Elaine also found a walk-in role in the legendary film The Battle of Algiers!

Her job at the RTA and capabilities as an interpreter brought her in contact with the visitors arriving in Algiers, the hub for liberation and antifascist organisations in the sixties. She knew many ANC activists who would pass through Algiers, including Oliver Tambo. She notes, “The South Africans invented a name for me in one of their languages – something on the order of ‘lifesaver’.”

Her bonds with Algeria were strong enough to weather Houari Boumediene’s coup in 1965 that overthrew Ben Bella. Under the new regime, “the press and APS were throttled”. Though not noted in the memoir, Boumediene’s entourage stood enthralled by Tito’s socialist model in Yugoslavia. Those independently minded and with a different vision for the nation – men like Malek Bennabi – were shunted aside. His short-lived spell as director of higher education came to an end and activities limited to conducting informal student seminars.

Elaine continued working for government media organisations and filing stories for the FLN newspaper, El Moudjahid. However, the authorities avoided to credit her by name because of “the tendency in the press to avoid foreign names, unless they were those of celebrities, or to ‘Arabize’ them to camouflage the shortage of qualified Algerian journalists”.

Elaine was closely involved in organising Stokely Carmichael’s visit to Algeria in 1967:

As his interpreter, I was on hand at the airport and attended his meetings with officials and journalists. His first words as he descended the stairs to the tarmac: “Here I am, finally, in the mother country” . . . While in Algiers, Stokely contacted the Guinean embassy and made arrangements to leave for Conakry. A trip that changed the course of his life. He was received there by President Ahmed Sékou Touré and his prominent permanent guest, Kwame Nkrumah, former president of Ghana, ousted by a coup d’état in 1966, a year after Ben Bella. Nkrumah became Stokely’s mentor until his death. Sékou Touré also introduced him to Miriam Makeba, the internationally known South African chanteuse . . . Stokely had fallen in love with Miriam; they would soon marry.

In this affair of the heart, Stokely betrayed Kathi Simms, an Afro-American from Philadelphia. It was left to Elaine to break the news to the jilted one when she arrived in Algiers en route to Conakry: “You will forget him, ‘I told her’, though I wasn’t so sure. She was a wonderfully intelligent, warm companion and I was sorry to see her leave Algiers.”

Now living in Guinea, Stokely Carmichael aka Kwame Ture became the honorary prime minister of The Black Panther Party (BPP), headed in the US by Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver. In April 1968, Cleaver was caught up in a shootout with the police in Oakland, California. He was wounded, while fellow Panther Bobby Hutton was killed. Three police officers were also wounded, and Cleaver was charged with attempted murder. To avoid incarceration and an inevitable death in the racist criminal justice system, he managed to escape to Cuba. However, after some months, he was “deemed too heavy a burden by his hosts” – and put on a flight to Algiers. Those in the know included Charles Chikerema, representative in Algiers of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union. Charles contacted Elaine: “Eldrige Cleaver is in town and needs help”. Thus began Elaine’s involvement with the BPP that lasted the seven years Cleaver remained in Algeria and subsequently in Paris. Elaine was able to observe Eldridge Cleaver’s behaviour and morals at close quarters, and the in-fighting within BPP:

I was in contact with Eldridge almost daily – through telephone calls, appointments, and visits. He often borrowed my car. When I was away, I left him the keys to the Austin and to my apartment. For him, I was neutral. He had no fear: I didn’t talk back, and I had no Panther role or history, no claims in the past or the future. There was no sexual connection between us, and he made it clear to everyone in his establishment that I was “out of bounds” for them too . . .Most important for Eldridge was that I spoke and wrote French. I was his key to the local establishment.

. . . early one morning in November, Eldridge turned up in my office at the Ministry of Information . . . he drew up a chair, sat down at the side of my desk, lowered his eyelids, and murmured: “I have something to tell you, something happened last night. I killed Rahim [Panther, aka Clinton Smith] . . . He stole all our money, stashed it, and was planning to split.” My head began to swim.

In 1968-69, Hoover’s FBI began stamping out BPP offices. In these harsh times, the US-based leader, Huey Newton, and Eldridge fell out, expelling each other from the Party. By 1971, Stokely Carmichael had distanced himself from the Panthers. Eldridge enraged Boumediene by sending an open letter to the media claiming the Algerians were not supporting him enough and thus betraying the revolution. Elaine notes that he had failed to understand he was living in a “semi-dictatorship”. The Panthers “saw themselves as free agents, able to deploy the powers of protest and the media as they wished.” His private life was in chaos: domestic violence toward his wife; mistresses; intimidation of colleagues. When a cache of US passports came his way, Eldridge Cleaver took the opportunity to disguise himself and slipped into France and sought political asylum in 1973. Elaine writes with regret that he chose to forget how much he owed his North African benefactors. She notes that his autobiography, Soul on Fire, published in 1978, contained references to his streetwise ways in Algiers – but “nothing could be further from the truth”.

This brings to mind Ebrahimsa Mohamed’s 1971 essay The Malcolm X I knew: “He [Malcolm] had none of the vices which plague people in organisations which function in his shadow. Many of the black power and socialist groups are made up of people who are extremely corrupt in their personal lives . . . [Malcolm] did and was prepared to face the situation in America like it was and is. He was in direct contact with the people. He never wanted to live outside of America and escape direct action. He saw America as the arena of action and did not want to use any outside country as a base” [Impact International, 24 September 1971].

Among the happier episodes in Elaine’s memoirs is the role she played in arranging the marriage of Ben Bella, to her colleague at the Ministry of Information, Zohra Sellami. Ben Bella, in captivity, had received authorisation from Boumediene to marry. However, the president was not happy with this match. Zohra’s father was escorted to Boumediene’s palace to discuss the matter:

He [Boumediene] implored her father to refuse to permit his daughter to marry the ex-president. His clincher: “Don’t you realise he is my enemy?” . . .

Zohra and I were waiting for her father when he returned from his meeting with Boumediene. Visibly moved, he repeated word for word their exchange. “My daughter is a free woman,” he had told the president. “I have always put my trust in her. When we lived in Paris, she was the only member of my family in whom I confided. She knew all about my militant activities, and I sometimes included her directly. On mission, she did her duty with courage. I cannot tell her who to marry. It’s her decision.

He was ushered out. The wedding took place in the little Sellami house, halfway up the winding rue Slimane Bedrani in the centre of Algiers – a wedding with a few guests, and no groom . . . a few days later, Zohra Sellami Ben Bella was driven – blindfolded again – to her husband’s residence, where she remained for three weeks. As she was not a prisoner and could not be permanently confined, arrangements were made for her to come back to Algiers to spend a week at her parent’s home, after which she returned to her husband for another three weeks, and so on. Except for Behja [Elaine’s work colleague] and I, Zohra’s friends withdrew from her, or looked the other way when she appeared . . . Zohra’s routine continued until Boumediene died in 1978.

In her own personal life, Elaine had drawn close to the Algerian Independence war veteran Mokhtar Mokhtefi, whom she met in 1972. She was deported from Algeria in 1974 due to her friendship with Zohra Ben Bella and took up residence in Paris. Mokhtar also left for France in 1975, warning friends that “Algeria was racing at top speed toward total control by forces of darkness”. His own memoir, J’Étais Français Musulman, Itinéraire d’un soldat de l’ALN , is also an important chronicle of the bravery of the rank and file within the FLN during the fighting and the rivalry between its zonal commanders.

The couple were to spend a contented life together, first running a jewelry shop on the Left Bank and then book shops, but once an activist, always an activist:

As soon as we sold the second Parisian bookshop in 1889, I became active with the Palestinian liberation movement, Ellen Wright [widow of Afro-American novelist Richard Wright] and I demonstrated every Saturday at place du Chatelet, where we were regularly insulted by passersby and motorists, one of whom tried to run her car into the militants on the square . . . I demonstrated at Les Halles with Americans Against the War, the war at the time being the Gulf War.

Elaine and Mokhtar later settled in New York. In 1990, the Algerian government lifted the visa bar on her. The tough cookie was soon back! Her vivid memoir is of interest not just as autobiography, but the way history is written and by whom. Much like Shirin Devrim’s A Turkish Tapestry, which tells the story of an Ottoman family adjusting to 1920s Turkey and its encounters with Mustafa Kamal Ataturk, her Algiers, Third World Capital – Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers, picks up details and nuances from a woman’s perspective. Such books solidify the role of women in the writing of history.

Jamil Sherif, August 2020