updated June 2020

On 10th December 1945, in one of his last acts as Governor of Sindh, Dow laid the foundation stone of a medical school in Karachi named after him – today the Dow University of Health Sciences. Perhaps the experts working on the teaching of colonialism in Pakistan’s schools need to assess whether this benevolent reputation is justified.

The region of Sindh – lying between Gujrat and Baluchistan – was occupied by British Raj in 1843 after defeating the local amirs. General Charles Napier, epitomising the imperial hubris and arrogance of the times, telegraphed his victory with the Latin ‘Peccavi’ – I have sinned. At first the region was part of the Bombay Presidency but in 1936 demarcated as a province in its own right, with a Governor reporting to the Viceroy in Delhi and the India Office in London. The port of Karachi and the downstream Indus was of strategic important to colonial interests. Control was paramount and dissidents were crushed. In 1942-43 atrocities were committed by British officials, on par with the suffering inflicted on the Moplas in South West India twenty years earlier, and on the Mau Mau in East Africa a decade after. The story of what happened in Sindh and the British colonial ‘scorched earth policy’ should not be forgotten, particularly at a time when there is a debate on the teaching of colonial history, warts and all.

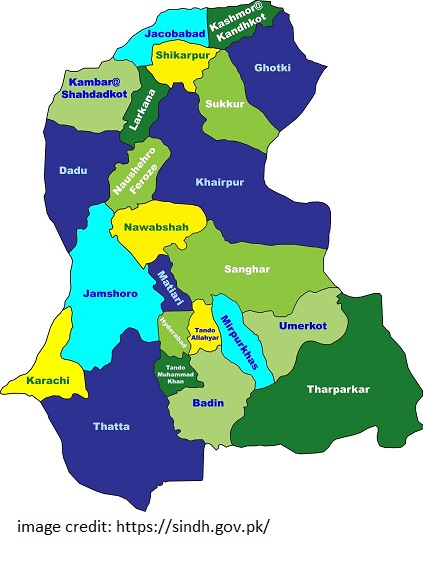

The Raj’s pretext for sending a military force into Sindh under Napier in the 1840s was the reluctance of the Amirs of Khairpur and Hyderabad to cede Karachi, Thatta, Sukkur, Rohri and other strategically placed and agriculturally rich towns along the Indus “for perpetuity”. The ruling Sindhi nobles were exiled first to Bombay and then Bengal. The mantle of resistance was taken by the sufi order of the Pirs of Pagaro – their followers were the ‘Hurs’. There seem to be two translations of this word – ‘holy’ and also ‘Free from slavery’. The authorities classified them as a ‘Criminal Tribe’, with reference to the Criminal Tribes Act, 1871. The Act was a licence to brutalise entire communities for any sign of ‘lawlessness’. Their situation was not helped by the conviction in 1930 of the sixth Pir of Pagaro, Pir Sibghatullah, and four followers for kidnap and wrongful confinement, notwithstanding the efforts of engaging the top lawyer of the time, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, led to the Raj imposing martial law. The Pir served a five-year sentence, to emerge from jail as a folk hero – Peter Mayne, in his travel account Saints of Sind, provides this account,

He was carried home in triumph in a train specially chartered by his Hurs, and within a short time he went on the Hajj to Mecca . . . he was much courted by politicians who knew that by a nod or a gesture he could direct the votes of thousands upon thousands . . . Soon after the declaration of World War II, rumours of a private army were current . . . Pir Sibghatullah was granting his Civic Guards the title of Ghazi – fighter in the cause of Allah and Islam.

There was a second Hur uprising, with attacks on government buildings and trains, and assassination of collaborators. The Pir was arrested in October 1941.

It is in this context that the Governor of Sind, Sir Hugh Dow, appointed his private secretary, Hugh Trevor Lambrick, as Additional District Magistrate in the Sindh interior, with what seems today unlimited powers and no accountability with respect to due process of law.

The historian Muhammad Umar Chand describes the consequences,

The conference held at the Government House [in Karachi] on 24 April 1942, discussed measures to be taken against the Hurs. Hugh Dow, the Governor, spoke of adopting the ‘scorched earth’ policy in Sindh, and his Secretary, Clee, echoed the sentiment. Among other things this conference decided ‘that Mr. Lambrick should be given a free hand to confiscate land and to destroy unauthorised hamlets belonging to the Faraki Hurs and to force them to live in selected villages . . . [and] orders should be promulgated prescribing the heaviest possible sentences for carrying or being found in possession of unlicensed arms.

However, even before this Conference, Lambrick’s reign of sadism had aleady commenced. Umar Chand notes,

On 12 April 1942 over 1,000 Hurs . . . who came to Police stations [under the requirement to register] of Shahadpur, Sanghar, Sinjhoro and Shahpur Chakar . . . were caught unawares and put in trains like sardines, and taken to be put to jail in Sukkur . . . Lambrick [goes on to say] ‘I think we must take the offensive not worrying over much about the likelihood of inflicting injury on a small proportion of harmless people . . . I do not think we should have the slightest scruple in rounding as many of the Hazri [registered Hurs] men as we can catch, and detaining them till things settle down”.

There was no consideration as to how their dependents would cope – a consequence of the dehumanisation. With the help of native informers, Lambrick hoped to draw the Hur brotherhood [Farakis and Ghazis] out in combat against the British Army, well-aware they were ill matched in weaponry. The bait was however not taken, but neither did ‘things’ settle down, and the Hurs regrouped in the Makhi Forest for a guerrilla warfare campaign. In May 1942 Lambrick ordered the destruction of the Pir’s home and the destruction of his follower’s villages – hundreds in the rural area of Sanghar. According to Umar Chand’s research, these atrocities took place ‘without any advance warning and without providing any alternate abode to the inmates. Eye witness accounts of this ruthless measure can be heard from the aged victims even today’.

Governor Hugh Dow adopted even more punitive measures by imposing martial law for a one-year period in June 1942, with Lambrick as civil administrator. The Pir was held in Hyderabad Jail, with immediate family members taken to a house on Bunder Road, Karachi, and kept in isolation. The request of the women to live with their families was refused. The Government now considered two options to deal with the Pir: either deportation [to Kenya or Abyssinia!], or ‘the possibility of trying him under special legislation for his known complicity in murder – the latter deemed more preferable, presumably referring to the 1930s case because the kidnapped person’s mother had been found killed. Peter Mayne notes,

. . . the trial was by court martial, behind locked doors. Very little was made public. Pir Pagaro was sentenced and hanged [in March 1943], and his body was taken for burial to a secret place . . . his ‘kot’ – the inner-citadel at Pir-jo-Goth – was razed to the ground, his library dispersed (the finest collection of Sindhi manuscripts extant, or so it was said) . . . his two sons were taken to England, there to be brought up like the sons of English gentlemen.

The Pir called on his defence lawyer of the past to take up his case for this second time, but Jinnah’s political commitments did not permit this commitment.

Complainants of Raj extra-judicial actions could not seek redress in the civil courts, due to an indemnification that applied during martial law. However, as this only commenced in June 1942 and was due to end in May 1943, Lambrick was vulnerable if someone raised a case against him for actions in the preceding two months. Governor Dow himself noted that the ‘action [that] was taken by him or under his order for which it would be difficult to find legal justification’. He too must have felt incriminated in Lambrick’s illegal actions. The Governor lobbied strenuously for the extension of the Indemnity Ordnance, but the Viceroy’s advice was either to lie low, or, ‘should a criminal case be brought against Lambrick, you can of course protect him by refusing to give sanction under Section 197 of the Criminal Procedure Code.’ The Viceroy added that if a civil suit be raised, it would be the Government’s duty to shoulder the expenses, including any damages, if awarded.

The Muslim ministers in the provincial government remained compliant, and no one else in Sindh had the means or will to hold Dow and Lambrick to account. However, in September 1942 the Prime Minister of Sindh, Allah Bukhsh Soomro, renounced his knighthood and other Raj accolades. not in protest over these miscarriages of justice, but rather a disparaging statement by Churchill on the ‘Quit India’. Dow dismissed him forthwith.

Lambrick retired from Government service in 1951, subsequently finding academic respectability as a fellow of Oriel College, Oxford. Not a word of his misdeeds! He even had the gall to write a novel entitled The Terrorist, dealing with the Hurs, proudly proclaiming that ‘the story has been pieced together from papers and other material collected during his years of service’.

His boss’s future career also had a touched of irony: in 1946 Hugh Dow was transferred to Palestine as Consul-General of Jerusalem – free to pursue his callousness on a different colonised population. David Cronin, in his commended Balfour’s Shadow, A Century of British Support for Zionism and Israel [PlutoPress, 2017] notes that Dow in this position “argued that allowing [Mufti] al-Husseini to have a ‘large influence’ in Palestine would be ‘quite fatal to any hope of an enduring settlement’ . In September 1948, Dow advised the Foreign Office . . . [it] should tell Arab governments that [King] Abdullah was preferable to the mufti, who would have an ‘openly hostile attitude’ to the new state of Israel.”

Jamil Sherif, March 2018; updated December 2019; updated June 2020

References

Mayne, Peter, Saints of Sind, London: John Murray, 1956

Chand,Muhammad Umar, ‘Indemnity sought for atrocities committed prior to Martial Law in Sindh 1942’, Quarterly Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, January – March 2004, Vol. LII No 1, pp. 103-133

Website of the Dow History Project click here